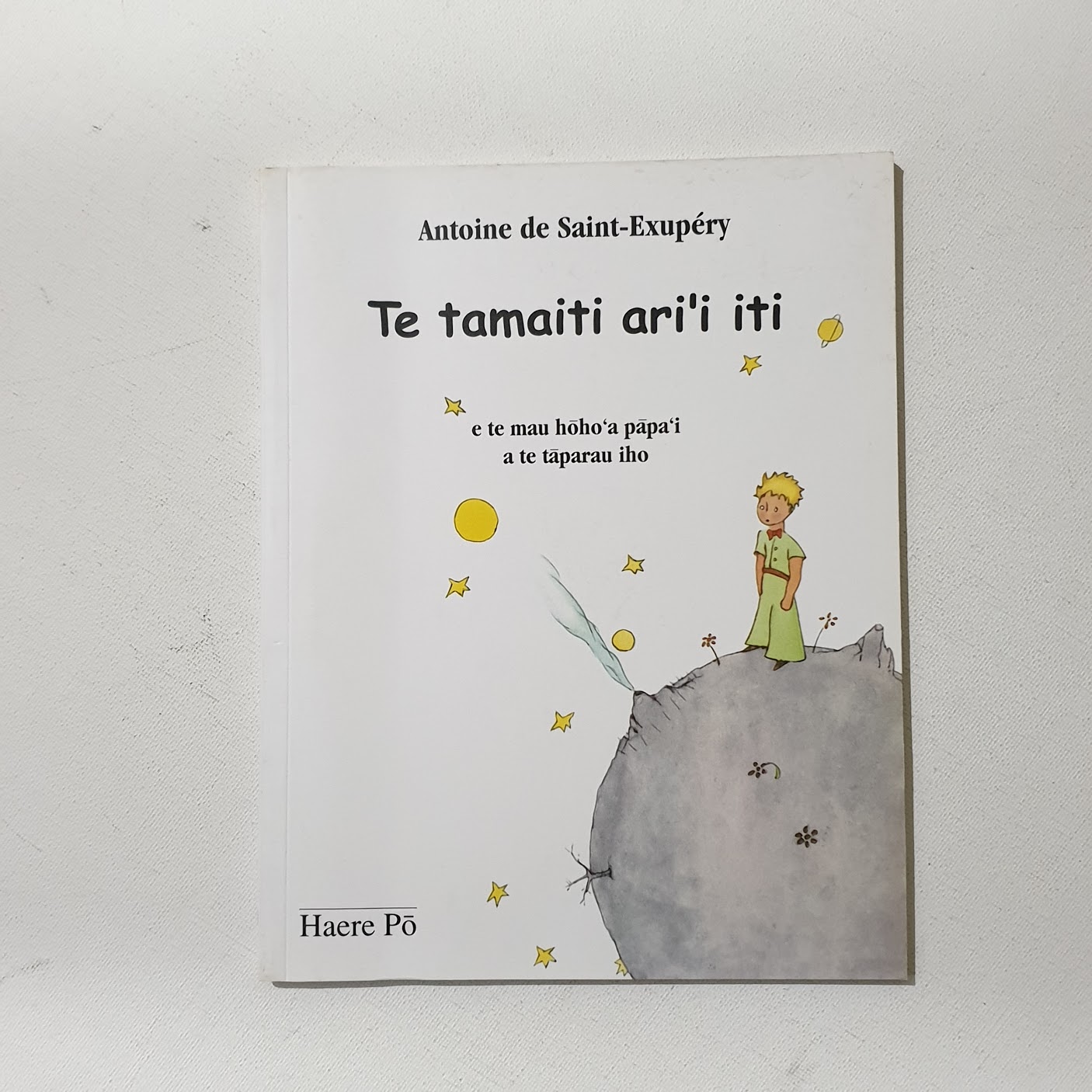

Te Tamaiti Ari’i Iti — in Tahitian language.

The Tahitian language, or Reo Tahiti, is a vibrant and melodic tongue of the Eastern Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family, spoken primarily in Tahiti and the Society Islands of French Polynesia. Historically, it served as a lingua franca across much of the central Pacific, particularly during the era of European exploration and missionary activity in the 18th and 19th centuries. Closely related to Hawaiian, Māori, and Rapa Nui, Tahitian shares many structural and lexical features with these sister languages but has developed its own unique rhythm and vocabulary. For example, the word for “love” in Tahitian is here, akin to aloha in Hawaiian and aroha in Māori—demonstrating the shared ancestral roots and poetic sensibility of the Polynesian language family.

Tahitian society was traditionally structured around extended families and chiefdoms, with language playing a vital role in oratory, poetry, genealogies, and the performance of sacred rituals. The spoken word was deeply revered, and skilled speakers were held in high esteem, often responsible for preserving and transmitting oral history. With the arrival of missionaries in the early 19th century, Tahitian was one of the first Polynesian languages to be written down using the Latin alphabet, and it became the medium for early Christian texts, including the Bible. For a time, Reo Tahiti was the dominant written and spoken language of the region, until French colonial policies began imposing French as the language of administration and education, leading to gradual erosion of Tahitian in formal settings.

Today, Tahitian remains widely spoken at home and in cultural contexts, although it has no official status equivalent to French. Nonetheless, there is a growing cultural and linguistic revival, driven by schools, media, and artists determined to reclaim and celebrate their heritage. The language is used in traditional music, dance (ʻori Tahiti), storytelling, and ceremonies, where its rich metaphorical and spiritual register comes to life. For example, manava (welcome) literally means “heart” or “spirit”, highlighting the deep interconnection between body, land, and emotion in Polynesian cosmology.

Tahitian’s influence extends well beyond its shores. As one of the foundational languages of the Polynesian triangle, it continues to play a role in shaping pan-Polynesian identity, both linguistically and culturally. Its relation to other Oceanic languages is not just genealogical but deeply felt—reflected in shared myths, seafaring traditions, and the enduring Polynesian worldview in which language is more than a tool: it is a vessel of mana, memory, and meaning.