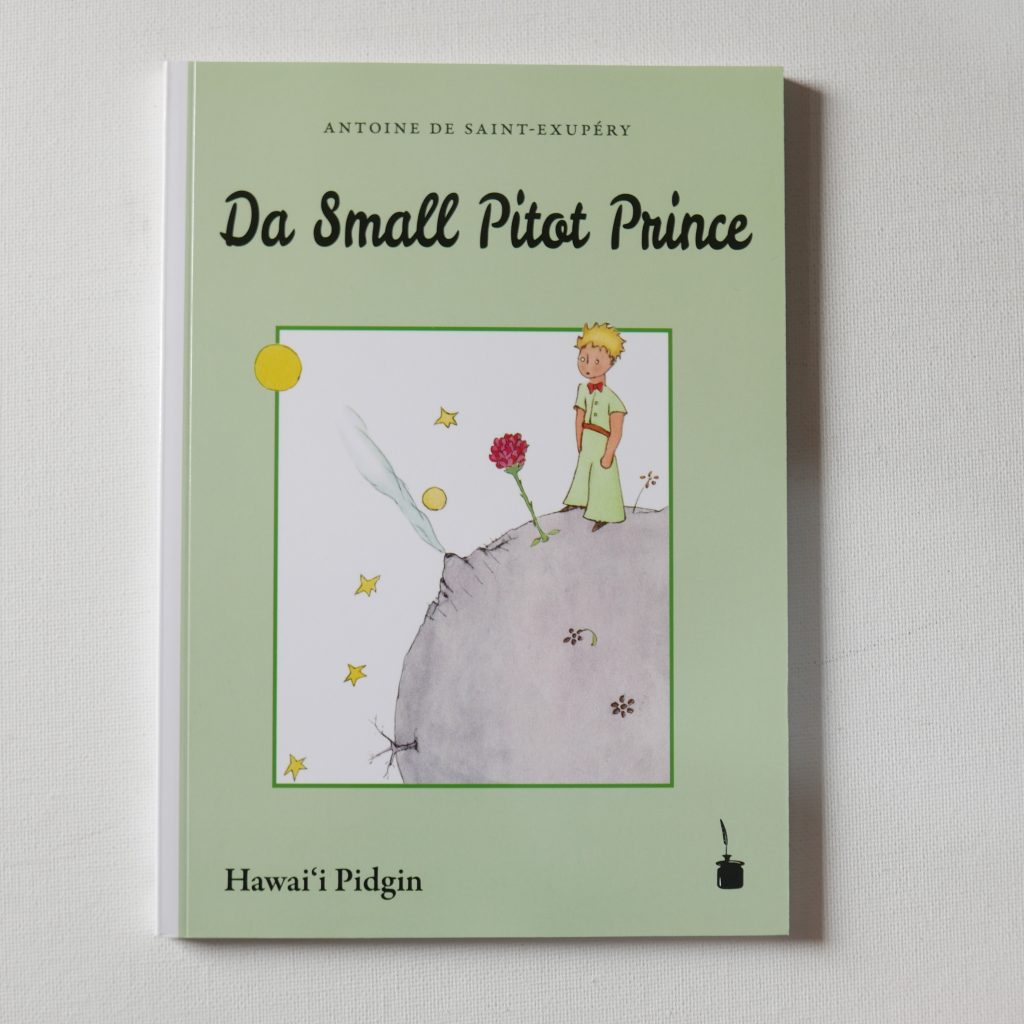

Da Small Pitot Prince – in Hawaii Pidgin.

Hawaiian Pidgin, more formally known as Hawai‘i Creole English, developed in the cultural and linguistic melting pot of the Hawaiian Islands. Emerging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it arose on sugarcane and pineapple plantations, where immigrant labourers from Japan, China, Portugal, the Philippines, Korea, and other nations worked alongside Native Hawaiians and English-speaking overseers. In order to communicate across these diverse groups, a simplified form of English—originally a pidgin, or contact language—gradually evolved into a fully-fledged creole with its own grammar, rhythm, and rich idiomatic expressions. Though English is its lexical base, Hawaiian Pidgin also draws heavily on Hawaiian, Japanese, Portuguese, and other languages, resulting in a vibrant, expressive, and distinctly local form of speech.

Culturally, Pidgin has long been a language of everyday life—spoken at home, in playgrounds, on the streets, and in local comedy, music, and literature. It reflects a multi-ethnic working-class identity, with a strong sense of shared experience, humour, and resistance to cultural erasure. For many, speaking Pidgin is not simply about communication but about belonging. A phrase like “No act, jus’ come chill” reveals both the linguistic economy and the casual, inclusive ethos of the language. Despite historical stigma—where Pidgin was long considered “broken English” and discouraged in schools—it is now recognised by many linguists as a legitimate creole language, and in 2015, it was added to the U.S. Census list of languages spoken at home.

The relationship between Hawaiian Pidgin and ʻŌlelo Hawai‘i (the Hawaiian language) is layered. While the two are structurally unrelated, they share a geographic and cultural space, and many Pidgin speakers are also advocates of Hawaiian cultural revival. Pidgin occasionally incorporates Hawaiian vocabulary and concepts, especially in informal or poetic speech, and serves as a bridge between English and Hawaiian identity, particularly for local-born residents of diverse ancestry. In literature and theatre, Pidgin has been powerfully used to express the lived realities of Native Hawaiians and local people, often critiquing colonisation, tourism, and economic inequality with sharp wit and authenticity.

Today, Hawaiian Pidgin remains widely spoken across the islands, from Honolulu to Hilo, by people of all ages and backgrounds. It lives not in grammar textbooks but in jokes, conversations, schoolyards, surf reports, and local rap lyrics—its intonation, syntax, and cultural reference points unmistakably Hawaiian in flavour.