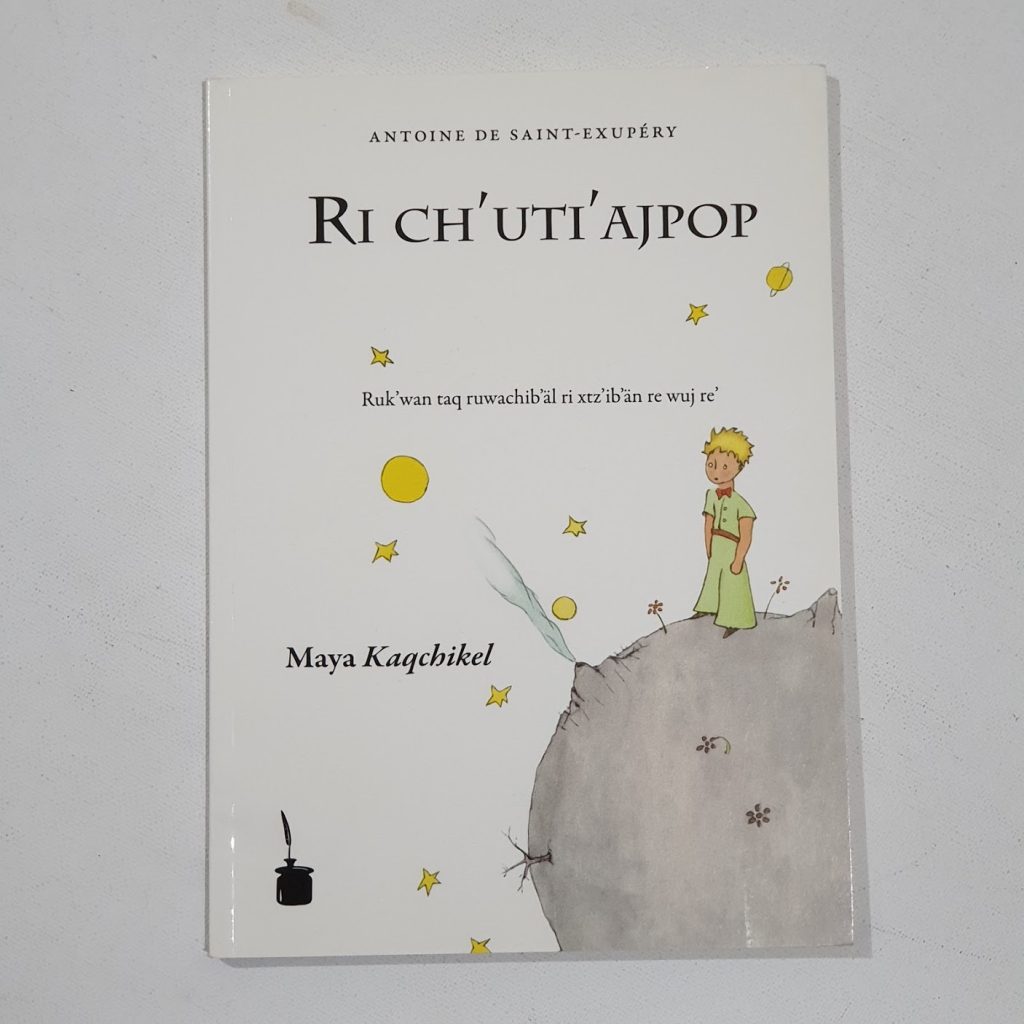

Ri Ch’uti’ajpop — in the Kaqchikel language.

The Kaqchikel language is one of the Mayan languages spoken by the Kaqchikel people, primarily in the central highlands of Guatemala. It is part of the broader Mayan language family, which is indigenous to Mesoamerica and has a rich cultural and historical context spanning thousands of years. The history of the Kaqchikel language and people is marked by resilience in the face of colonisation, dictatorship, and even massacre.

Kaqchikel is a member of the K’ichean branch of the Mayan language family. This family is one of the most well-documented indigenous language families in the Americas, with a rich tradition of written and oral literature. The K’ichean branch also includes languages such as K’iche’ (Quiché), Tz’utujil, Sakapulteko, and Sipakapense. These languages are closely related and share many linguistic features, though each has its own distinct characteristics and dialects.

Like other Mayan languages, Kaqchikel is an ergative-absolutive language, meaning it has a grammatical structure where the subject of an intransitive verb is treated like the object of a transitive verb, rather than the subject of a transitive verb, as in nominative-accusative languages like English. The language is highly agglutinative, meaning it uses affixes (prefixes, suffixes, and infixes) extensively to convey grammatical relationships and meanings. Kaqchikel is also known for its use of a complex system of verb conjugation that changes depending on the person, number, tense, aspect, mood, and voice.

The Mayan civilisation, including the Kaqchikel people, developed a sophisticated writing system that combined logograms and syllabic symbols. Although much of the original Kaqchikel writing was lost due to Spanish colonisation, the tradition of written language continues, and modern efforts have been made to standardise the orthography of Kaqchikel using the Latin alphabet.

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the Kaqchikel people were part of the larger Maya civilisation, which was characterised by its advanced achievements in mathematics, astronomy, architecture, and art. The Kaqchikel had their own city-states, with Iximche being one of the most significant. Iximche was a powerful city-state and served as the capital of the Kaqchikel kingdom. The Kaqchikel were closely related to the K’iche’ people, but they eventually became rivals, leading to conflicts and shifting alliances among the various Maya groups.

The Kaqchikel society was organised into a hierarchical structure with a ruling class, priests, and commoners. The rulers were often seen as intermediaries between the gods and the people, and they played a central role in both political and religious life. Religion was deeply intertwined with daily life, and the Kaqchikel, like other Maya groups, practiced a complex religion that included the worship of numerous gods, rituals, and ceremonies tied to the agricultural calendar.

The Kaqchikel initially allied with the Spanish conquistadors under Pedro de Alvarado to defeat their traditional enemies, the K’iche’. However, once the K’iche’ were subdued, the Kaqchikel themselves were betrayed and subjugated by the Spanish. The Spanish conquest led to the destruction of many Kaqchikel city-states, including Iximche, which was eventually abandoned as the Kaqchikel retreated to more remote areas to resist Spanish rule. The Spanish imposed their own culture, language, and religion on the Kaqchikel people. The Catholic Church played a significant role in this process, forcibly converting the Kaqchikel to Christianity and suppressing their traditional religious practices. Many aspects of Kaqchikel culture were lost or syncretized with Christian practices, but some elements of their traditional religion and customs have survived to this day.

In the 20th century, Guatemala experienced a series of U.S.-backed dictatorships, particularly during the Cold War, when the U.S. government supported right-wing military regimes to prevent the spread of communism in Latin America. These regimes were characterised by extreme repression, including the targeting of indigenous communities like the Kaqchikel, The Guatemalan military, supported by U.S. aid, carried out widespread human rights abuses against the indigenous Maya population, including the Kaqchikel. This period, particularly during the regimes of military dictators like Efraín Ríos Montt, saw systematic violence against Maya communities. The violence included massacres, forced disappearances, torture, and the destruction of entire villages. The Kaqchikel, along with other Maya groups, were disproportionately affected by these atrocities.

The violence and displacement during this period led to the disruption of traditional ways of life, including the transmission of the Kaqchikel language and culture. Many Kaqchikel people were forced to flee their homes, leading to the loss of language and cultural practices among displaced populations. Despite these challenges, the Kaqchikel people have continued to preserve their language and culture, often in the face of great adversity.

The most intense period of violence against the Maya people, including the Kaqchikel, occurred during the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996). The government’s counterinsurgency strategy included acts of genocide against the indigenous population, with the intent of eradicating support for leftist guerrillas. Efraín Ríos Montt’s regime (1982-1983) was particularly notorious for its “scorched earth” campaigns, which resulted in the massacre of tens of thousands of Maya people. These campaigns aimed to destroy the social and cultural fabric of Maya communities, including the Kaqchikel.

Despite the systematic attempts to erase their culture, the Kaqchikel people have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Efforts to revive and maintain the Kaqchikel language have continued, with programs aimed at teaching the language in schools, producing literature in Kaqchikel, and promoting its use in both public and private life. The Kaqchikel language has become a symbol of resistance and cultural survival, with many Kaqchikel people viewing the preservation of their language as an act of defiance against the historical forces that sought to destroy their identity.

Since the end of the Guatemalan Civil War, there have been concerted efforts to revitalise Kaqchikel and other Mayan languages. These efforts include the establishment of language programs, the creation of educational materials, and the promotion of Kaqchikel in media and public discourse. The Kaqchikel people, along with other Maya groups, have also sought justice for the atrocities committed during the civil war, including the recognition of the genocide against the Maya and efforts to preserve the memory of those who were lost.

Today, Kaqchikel is spoken by around half a million people, primarily in the central highlands of Guatemala. The language continues to be a vital part of the cultural identity of the Kaqchikel people. There are ongoing efforts to document the language, produce literature and educational materials, and integrate Kaqchikel into the national curriculum to ensure its survival for future generations.

The struggles and resilience of the Kaqchikel people have gained international recognition, particularly in the context of human rights. Efforts to bring attention to the genocide and ongoing challenges faced by the Maya people, including the Kaqchikel, have contributed to a greater global awareness of indigenous issues in Guatemala.