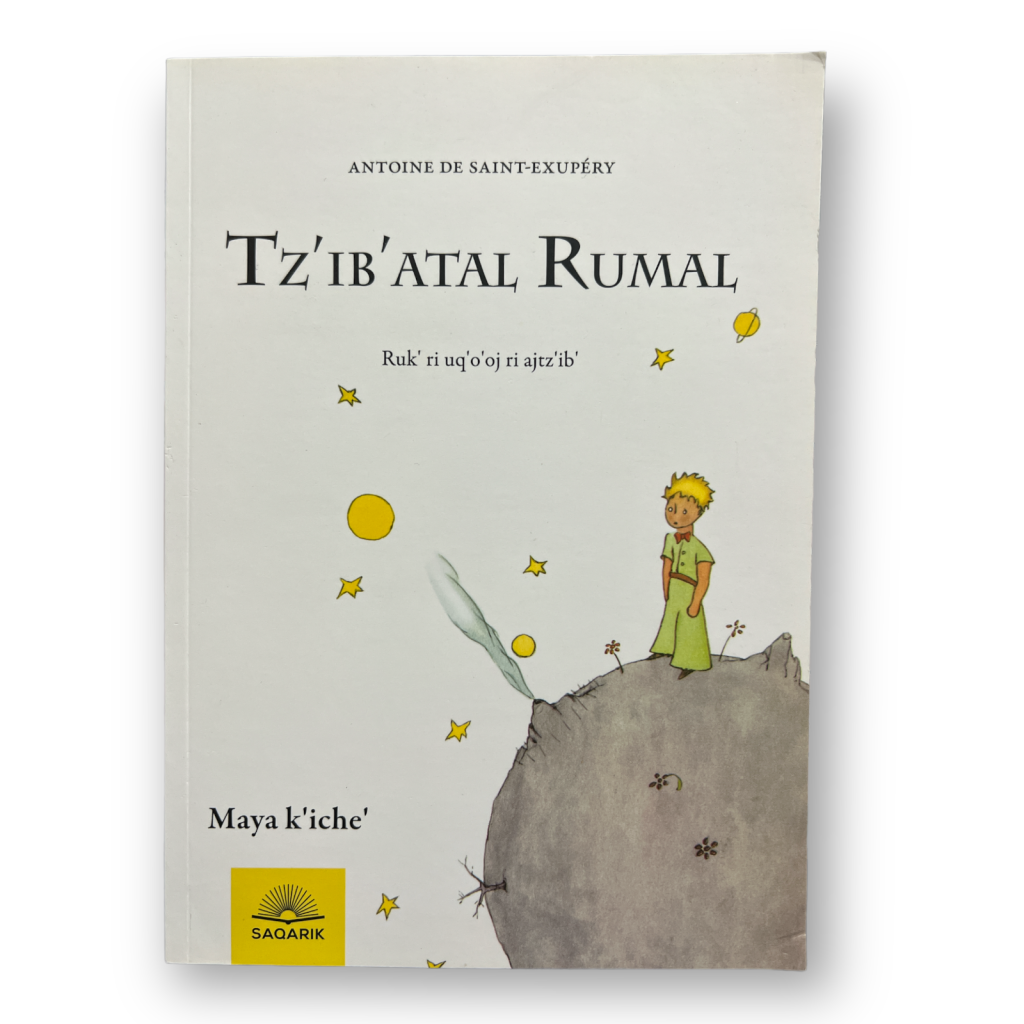

Tzʼibʼatal Rumal — in Maya Kʼicheʼ.

The K’iche’ (also spelled Quiché) language is one of the most prominent and widely spoken Mayan languages, with a significant cultural and historical legacy. It is primarily spoken by the K’iche’ people in the central highlands of Guatemala. The history of the K’iche’ language and people spans from the heights of pre-Columbian civilisation to the struggles of the 20th century during periods of political repression and violence. Below is a detailed exploration of the K’iche’ language, its relation to other Mayan languages, and its historical and cultural context before, during, and after Spanish colonisation, including the periods of U.S.-backed dictatorships and the genocide of the Maya people in Guatemala.

K’iche’ is a member of the K’ichean branch of the Mayan language family, which also includes other closely related languages like Kaqchikel, Tz’utujil, Sakapulteko, and Sipakapense. The Mayan language family is one of the oldest and most well-documented language families in the Americas, with roots that go back thousands of years.

K’iche’ is an ergative-absolutive language, a common feature among Mayan languages. In this system, the subject of an intransitive verb is treated like the object of a transitive verb. The language is highly agglutinative, using prefixes, suffixes, and infixes to convey various grammatical relationships such as person, number, tense, aspect, mood, and voice. K’iche’ has a complex system of verb conjugation and noun classification, with verbs typically agreeing with both the subject and object in terms of person and number.

K’iche’ is closely related to other languages in the K’ichean branch, particularly Kaqchikel and Tz’utujil, which share many grammatical structures and vocabulary with K’iche’. However, each language has its own distinct characteristics and variations. The languages of the K’ichean branch are mutually intelligible to varying degrees, especially among speakers in regions where these languages are in close contact. The K’iche’ people, like other Maya groups, developed a sophisticated writing system that combined logograms with syllabic signs. Although much of the original Maya script was lost or destroyed during Spanish colonisation, K’iche’ has a strong oral tradition and a significant corpus of written literature that has survived and continues to be produced today.

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the K’iche’ people were one of the dominant groups in the Maya civilisation. They established powerful city-states in the Guatemalan highlands, with the city of Q’umarkaj (also known as Utatlán) serving as their capital. The K’iche’ were known for their advanced knowledge of astronomy, mathematics, and architecture. They built large ceremonial centers with pyramids, palaces, and ball courts, reflecting their sophisticated culture and religious practices.

The K’iche’ society was highly organised, with a complex social hierarchy that included nobility, priests, warriors, artisans, and commoners. The ruling class maintained power through alliances, warfare, and religious authority. Religion played a central role in K’iche’ society, with the K’iche’ practicing a polytheistic religion that involved the worship of numerous gods associated with natural elements, agriculture, and celestial bodies. The Popol Vuh, often referred to as the “Maya Bible,” is one of the most important works of K’iche’ literature. It is a sacred text that recounts the creation of the world, the deeds of the gods, and the history and mythology of the K’iche’ people. The Popol Vuh was originally passed down orally but was later transcribed in the K’iche’ language using the Latin alphabet in the 16th century. It remains a crucial cultural and religious document for the K’iche’ and other Maya peoples.

The K’iche’ were among the first Maya groups to encounter the Spanish conquistadors. In 1524, Pedro de Alvarado led a brutal campaign against the K’iche’, culminating in the defeat of their forces and the destruction of Q’umarkaj. The K’iche’ people were subjugated by the Spanish, who imposed their language, religion, and culture on the indigenous population. Many K’iche’ were forced into labor under the encomienda system, and their traditional way of life was severely disrupted. The Spanish sought to eradicate the traditional religious practices of the K’iche’ and replace them with Christianity. Catholic missionaries destroyed many Maya religious texts and artefacts, but the K’iche’ managed to preserve some of their cultural and religious practices through syncretism, blending Christian elements with their indigenous beliefs. Despite the suppression, the K’iche’ language survived and continued to be spoken in rural areas, where it was used to maintain cultural continuity and resist Spanish domination.

Throughout the colonial period, the K’iche’ people engaged in various forms of resistance, including revolts and maintaining their language and cultural practices in secret. The K’iche’ adapted to Spanish rule by incorporating certain aspects of Spanish culture while preserving their own identity, leading to a unique blend of indigenous and colonial influences in their language, religion, and social structures.

In the 20th century, Guatemala experienced a series of U.S.-backed military dictatorships, particularly during the Cold War. These regimes were characterised by extreme repression, especially against indigenous communities like the K’iche’. The Guatemalan government, with support from the United States, implemented harsh counterinsurgency strategies aimed at crushing any opposition to the regime. This led to widespread human rights abuses, particularly against the indigenous population.

Repression and Human Rights Violations. During the regimes of dictators like Carlos Castillo Armas and later, General Efraín Ríos Montt, the K’iche’ people faced severe repression. The military and paramilitary forces targeted K’iche’ communities, labelling them as insurgent sympathisers and subjecting them to violent reprisals. The repression included massacres, forced disappearances, torture, and the destruction of entire villages. Indigenous leaders, activists, and intellectuals who advocated for indigenous rights were often targeted, leading to the loss of many cultural and community leaders.

The violence and displacement during this period disrupted the transmission of the K’iche’ language and culture. Many K’iche’ people were forced to flee their homes, leading to a decline in the use of the language among displaced populations. Despite these challenges, the K’iche’ people continued to preserve their language and cultural practices as acts of resistance. The K’iche’ language became a symbol of identity and resilience in the face of systematic attempts to erase their culture.

The most intense period of violence against the K’iche’ and other Maya people occurred during the Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996), particularly under the regime of General Efraín Ríos Montt. His government carried out a “scorched earth” policy aimed at eliminating any support for leftist guerrillas, resulting in widespread massacres of indigenous communities.

Ríos Montt’s counterinsurgency campaigns, which were supported by U.S. military aid and training, led to the systematic destruction of over 600 indigenous villages. Tens of thousands of Maya people, including the K’iche’, were killed, and many more were displaced or forced into refugee camps.

Despite the atrocities committed during the civil war, the K’iche’ people have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Efforts to preserve the K’iche’ language continued, with programs aimed at teaching the language in schools, producing literature in K’iche’, and promoting its use in public life.

The K’iche’ language became a powerful tool for organising resistance and preserving cultural identity. Community leaders, educators, and activists played crucial roles in revitalising the language and using it as a means of advocating for indigenous rights.

After the signing of the peace accords in 1996, there has been a renewed focus on revitalising the K’iche’ language and culture. Indigenous organisations and international NGOs have supported efforts to document the language, produce educational materials, and promote K’iche’ in media and public discourse. The K’iche’ people have also sought justice for the crimes committed during the civil war, including the recognition of the genocide against the Maya. These efforts have contributed to a broader movement for indigenous rights and cultural preservation in Guatemala.

Today, K’iche’ is spoken by over a million people, making it the most widely spoken Mayan language in Guatemala. The language continues to be a vital part of the cultural identity of the K’iche’ people and is used in education, media, and daily life. Ongoing efforts to document and standardise the K’iche’ language have led to the creation of dictionaries, grammar books, and other resources that support language learning and literacy.

The struggles and resilience of the K’iche’ people have gained international recognition, particularly in the context of human rights. Efforts to bring attention to the genocide and ongoing challenges faced by the K’iche’ and other Maya groups have contributed to a greater global awareness of indigenous issues in Guatemala.