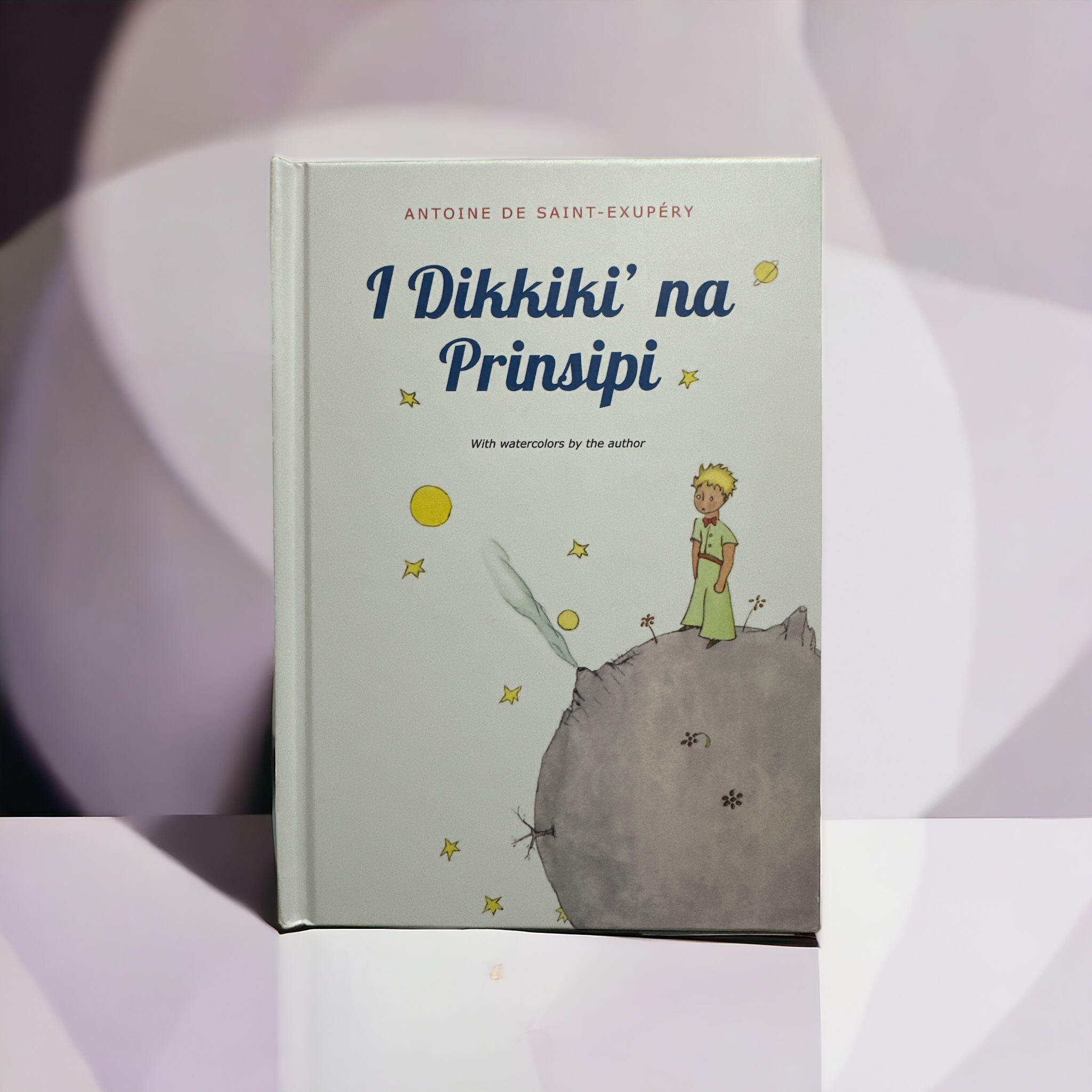

I Dikkiki’ na Prinsipi — in Chamorro language.

The Chamorro language, or Finu’ Chamoru, is the indigenous tongue of the Chamorro people, the original inhabitants of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands in the western Pacific. As a member of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family, Chamorro shares distant linguistic ties with other Oceanic and Southeast Asian languages, such as Tagalog, Malay, and Hawaiian. However, what sets Chamorro apart is its long and complex history of colonial influence, particularly from Spanish, which ruled the Marianas from the 17th century until the late 19th. This resulted in a unique linguistic blend—while Chamorro grammar remains largely Austronesian, its vocabulary is heavily infused with Spanish loanwords. For instance, na’an (name) is Austronesian in origin, but sakkate (from Spanish sacar, “to take out”) is a clear example of lexical borrowing.

Historically, the Chamorro language was central to a rich seafaring, matrilineal culture, where oral traditions, ancestral chants (kantan chamorrita), and place-based knowledge were passed down through generations. The language reflected the islanders’ close relationship with the sea, land, and community. Following American acquisition of Guam in 1898 and the Northern Marianas’ shifting governance under German, Japanese, and later American control, English began to replace Chamorro in education and public life, especially after World War II. This shift led to a decline in intergenerational transmission, and today, although many Chamorros identify strongly with the language, fluent speakers are increasingly elderly, and the language is classified as critically endangered.

Culturally, Chamorro remains deeply embedded in local traditions—family gatherings, fiesta culture, Catholic ceremonies, and storytelling all carry traces of its rhythm and spirit. Contemporary Chamorro identity often balances both indigenous pride and diasporic adaptation, especially as many Chamorros live abroad in Hawaii and the mainland United States. The language plays a crucial role in cultural expressions such as dance (ché’lu), proverbs, and oral history, which continue to reinforce a collective sense of belonging.

In its linguistic landscape, Chamorro stands at a crossroads of Austronesian, Spanish, and English influences, forming a kind of cultural palimpsest that tells the story of centuries of contact, colonisation, and survival. Its nearest indigenous linguistic relatives, such as Palauan, are also Austronesian but have developed along separate historical paths. In the face of ongoing globalisation and political ambiguity, Chamorro today serves not only as a means of communication but as a symbol of resistance, heritage, and renewal—a living link to a past that continues to shape the present and inspire future generations across the Mariana archipelago and beyond.