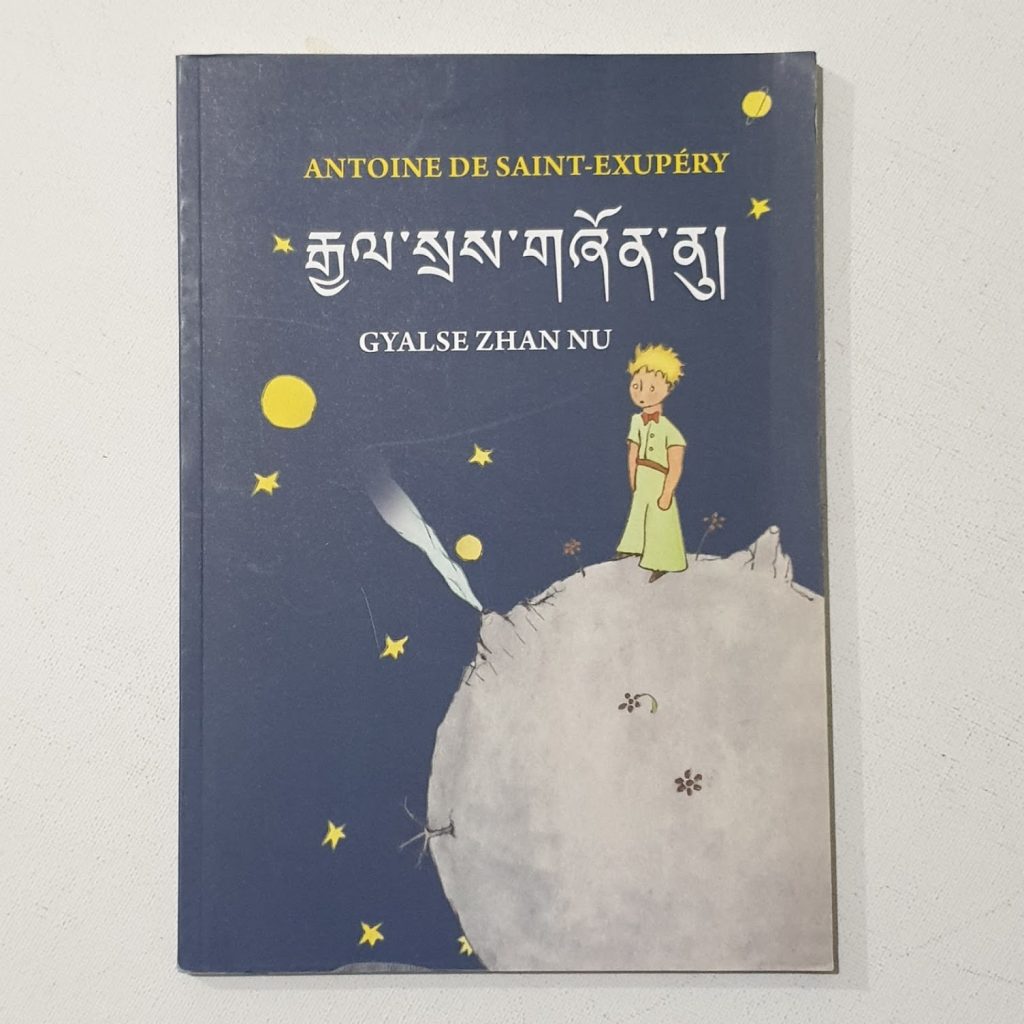

Gyalse Zhan Nu — in Dzongkha.

Dzongkha, the national language of Bhutan, is a fascinating and deeply symbolic tongue that embodies the spiritual, historical, and cultural heart of this Himalayan kingdom. Literally meaning “the language of the fortress” (dzong referring to Bhutan’s iconic monastic-fortress architecture), Dzongkha belongs to the Bodish branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family and is closely related to Classical Tibetan, as well as to other regional languages like Sikkimese and Sherpa. Emerging from centuries of Buddhist scholarship and mountain trade, Dzongkha developed as the administrative and liturgical language of Bhutan’s dzongs—centres of both governance and religion—binding together the country’s diverse highland communities under a shared cultural and spiritual framework.

Historically, Dzongkha’s rise to national prominence was tied to Bhutan’s consolidation as a unified state in the 17th century under Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal, who established the dual system of governance balancing monastic and secular authority. The language, used in both religious rituals and secular administration, became a marker of national identity, distinct from the neighbouring Tibetan polities, while still retaining deep linguistic and cultural ties to the broader Tibetan world. Culturally, Dzongkha-speaking societies are steeped in Buddhist values, with a worldview shaped by reverence for nature, impermanence, and communal harmony. Language is tightly interwoven with ritual, from monastic chants and sacred texts to folk songs, proverbs, and oral storytelling traditions that pass down moral lessons, historical memory, and local lore.

In relation to other Sino-Tibetan languages, Dzongkha shares a strong structural resemblance to Classical Tibetan, particularly in its use of honorific forms, complex verb systems, and tonal distinctions, yet it has developed its own distinct phonetic character and lexical innovations over centuries of geographic and political separation. It is surrounded by a rich mosaic of smaller Bhutanese languages—such as Tshangla, Khengkha, and Bumthangkha—with which it coexists, often in a multilingual environment where Dzongkha serves as a unifying national medium. Politically and educationally, Dzongkha has been promoted since the late 20th century as part of Bhutan’s efforts to preserve national culture in the face of globalisation, enshrined as the language of government, media, and public education, while English is used extensively in secondary education and international affairs.

To speak Dzongkha today is to participate in a living cultural heritage that reflects Bhutan’s unique path of measured modernisation—where Gross National Happiness is prioritised alongside economic development, and where language serves not merely as communication but as a vessel of identity, tradition, and national unity. Whether chanted in mountain monasteries, taught in village schools, or heard in the lively markets of Thimphu, Dzongkha carries within it the pulse of a people whose linguistic landscape remains beautifully entwined with their spiritual and cultural roots.