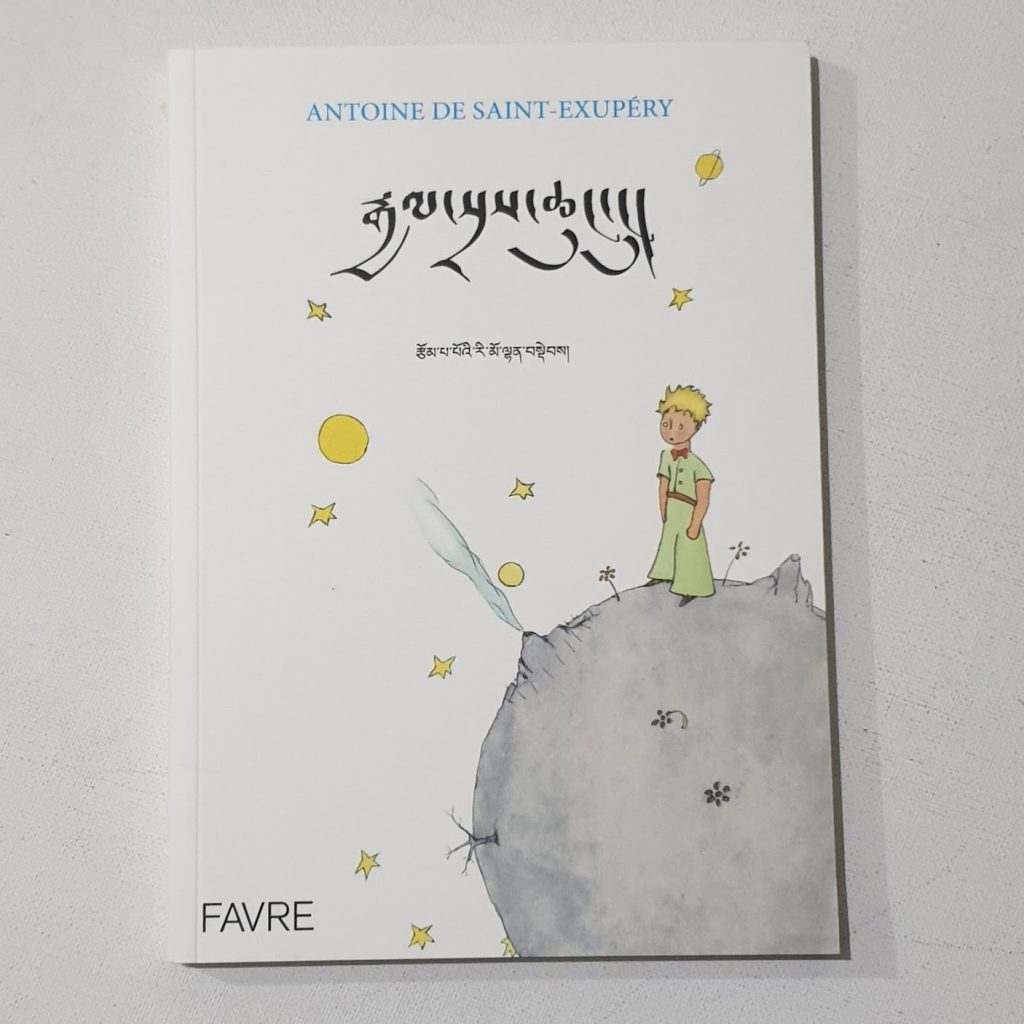

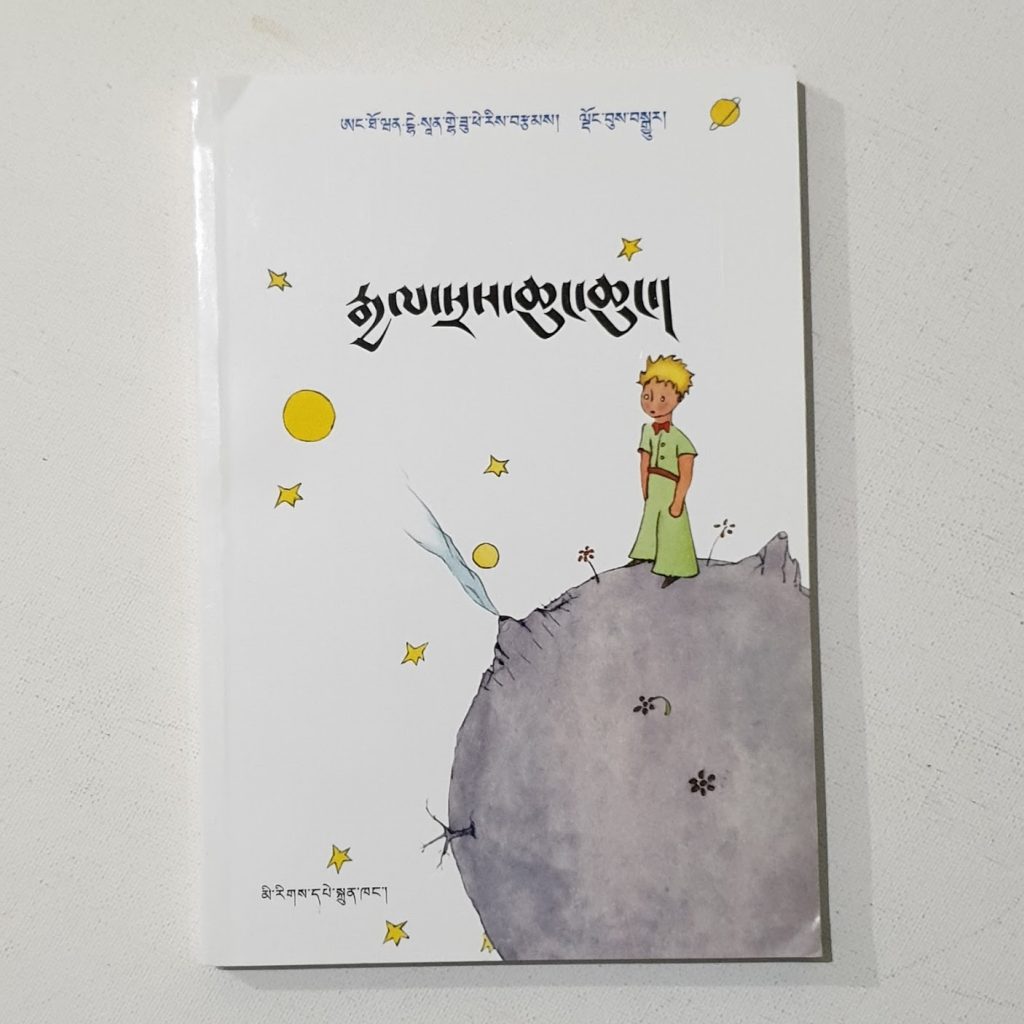

རྒྱལ་སྲས་ཆུང་ངུ་། — in Tibetan.

The Tibetan language, known as Bod skad in its native form, is one of the most captivating and historically profound languages of the Sino-Tibetan family, serving as the linguistic and cultural backbone of the vast Tibetan Plateau. With its origins rooted in the early centuries of the first millennium CE, Tibetan developed not only as a medium of daily communication but as a sophisticated literary and religious language, particularly after the creation of the Tibetan script in the 7th century under King Songtsen Gampo. Modelled partly on Indian scripts to translate Buddhist texts, Tibetan became the sacred vehicle through which Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhist teachings were transmitted, copied, and studied across Central Asia, Mongolia, Bhutan, Sikkim, and Ladakh, creating a shared cultural-religious sphere that extended far beyond the political borders of Tibet itself.

Culturally, Tibetan-speaking societies are deeply embedded in a worldview shaped by Buddhist philosophy, with language serving as both a spiritual tool and a cultural mirror. Tibetan carries layers of ritual, oral storytelling, and poetic expression, whether in the chants of monks in high-altitude monasteries, the folk songs of nomadic herders, or the proverbs and sayings passed down through families. It is a tonal language with a complex system of honorifics, reflecting the importance of social hierarchy, respect, and religious devotion. Across the Tibetan Plateau, regional dialects—such as Central Tibetan (Lhasa dialect), Amdo, and Kham—show striking variation, some of which are not mutually intelligible, yet all retain a deep connection to Classical Tibetan, the literary and liturgical form that unites the broader Tibetan Buddhist world.

In relation to other Sino-Tibetan languages, Tibetan stands alongside Burmese and the various Himalayan and Qiangic languages as part of the Tibeto-Burman branch, sharing ancient grammatical roots while having evolved its own distinct script, phonology, and cultural identity. To speak or study Tibetan today is to enter a world where language is inseparable from spirituality, memory, and resistance—a linguistic tradition that carries within it centuries of philosophical reflection, artistic expression, and the enduring resilience of a people whose culture is intricately bound to the snowy mountains, wide-open grasslands, and deep spiritual traditions of one of the world’s most remarkable civilisations.