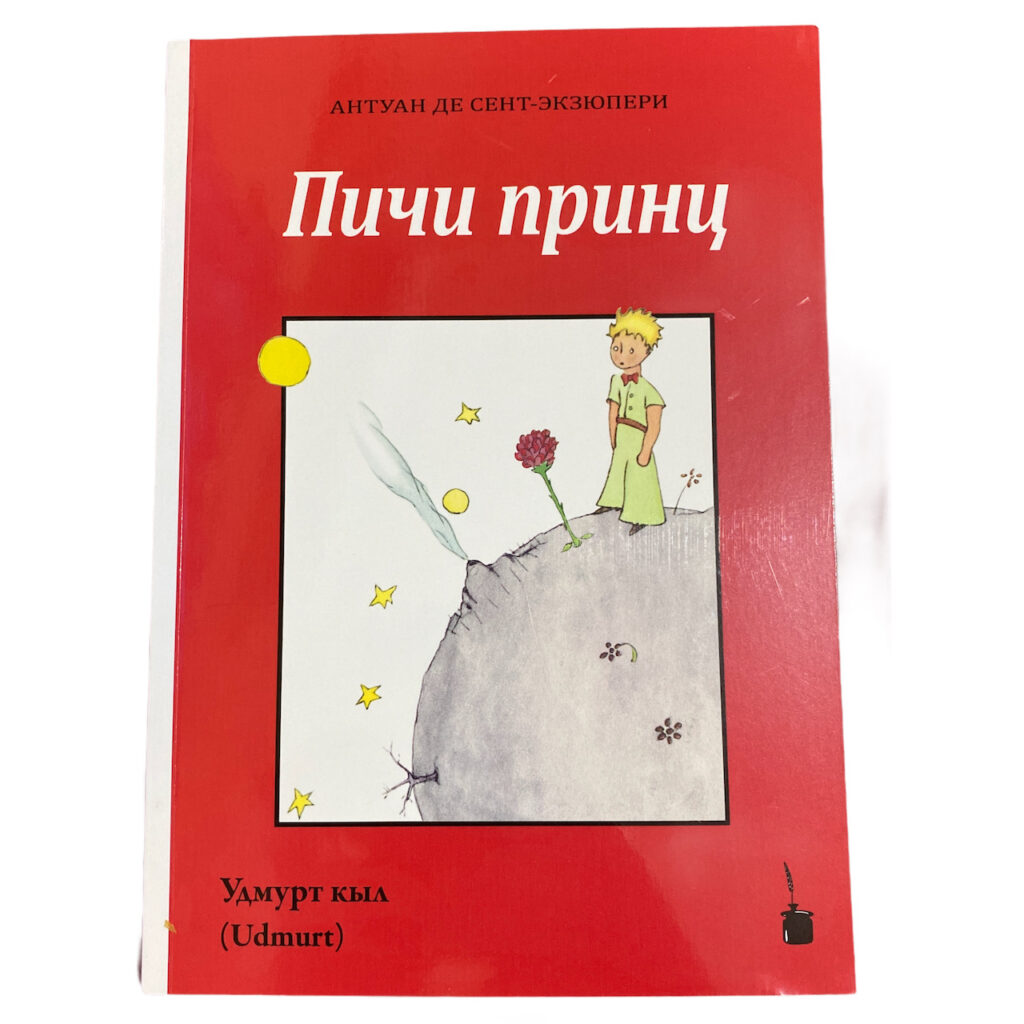

Пичи Принц / Pici Prints — in Udmurt.

The Udmurt language, or удмурт кыл (udmurt kyl), is a member of the Permic branch of the Uralic language family, making it a linguistic cousin to Komi and a more distant relative to Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian. Spoken primarily in the Udmurt Republic of the Russian Federation, nestled between the Kama and Vyatka rivers, Udmurt is an agglutinative language with complex case systems, vowel harmony, and a rich set of suffixes that allow for expressive precision and poetic construction. Historically, Udmurt has evolved in the shadow of larger political and linguistic forces—particularly Russian—and yet it carries with it echoes of an ancient Uralic heritage rooted in the forests and rivers of the Volga basin. The earliest written records of the language appeared in the 18th century, but oral tradition long preceded it, with a wealth of folklore, epic songs, and animist cosmology preserved in the musical cadence of Udmurt speech.

Culturally, the Udmurt people possess a vibrant identity that balances their Finno-Ugric origins with centuries of interaction with Slavic, Turkic, and Tatar neighbours. Their spiritual traditions were traditionally animist and shamanistic, with a deep reverence for nature, seasonal cycles, and ancestral spirits—a worldview that continues to infuse modern cultural expressions. Udmurt folk music, with its haunting polyphony and use of traditional instruments like the krez’, stands out as one of the most distinctive in the Uralic world. Rituals, such as the springtime gerber fertility festival, and the colourful national dress reflect a cultural richness that remains proudly maintained in rural communities.

Educationally and politically, however, Udmurt has faced significant challenges. During the Soviet era, a brief flowering of Udmurt-language education and publishing was soon curtailed by policies of Russification, which prioritised Russian as the language of power, science, and progress. Although Udmurt remains an official language of the republic, in practice its usage is limited: Russian dominates in schools, media, and urban life, and fluency in Udmurt is declining, especially among younger generations. Despite some institutional support—including language classes, local publishing, and cultural institutions—Udmurt is classified by UNESCO as a vulnerable language.

In its linguistic form and cultural ethos, Udmurt remains unmistakably tied to the broader Uralic family. It shares structural affinities with Komi and Mari, and deeper typological similarities with Finnish and Hungarian, especially in its agglutinative grammar and love of metaphor and mood. Yet what makes Udmurt truly compelling is its quiet, stoic endurance—a language of the forest edge, carried by a people who, despite marginalisation, continue to sing, write, and dream in their ancestral tongue. Speaking Udmurt today is not merely a cultural act—it is a statement of survival, an assertion of dignity, and a living link to a pre-Russian past that remains alive beneath the surface of modern life.