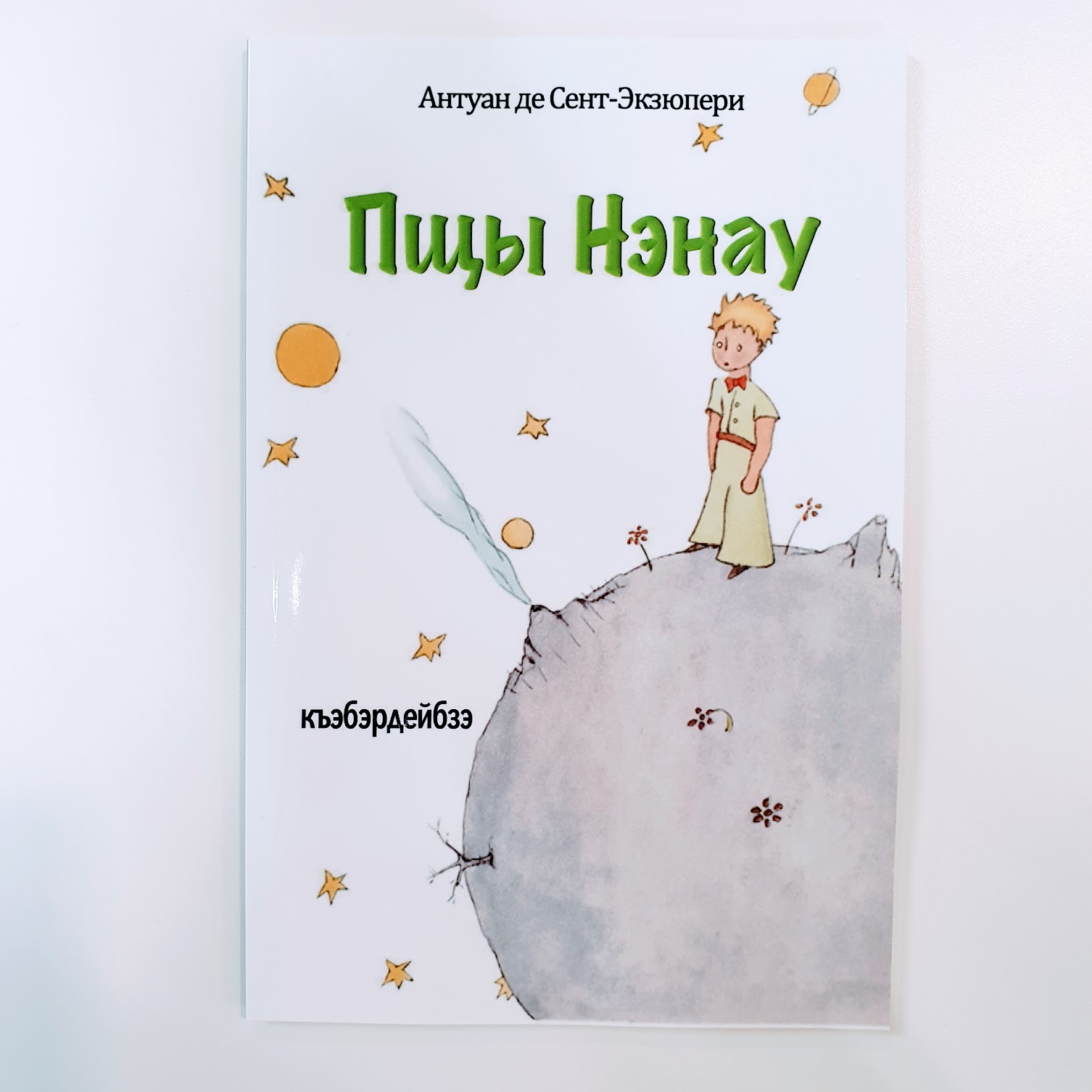

Пщы Нэнау и Псысэ — Pshchy Nenau i Psyse.

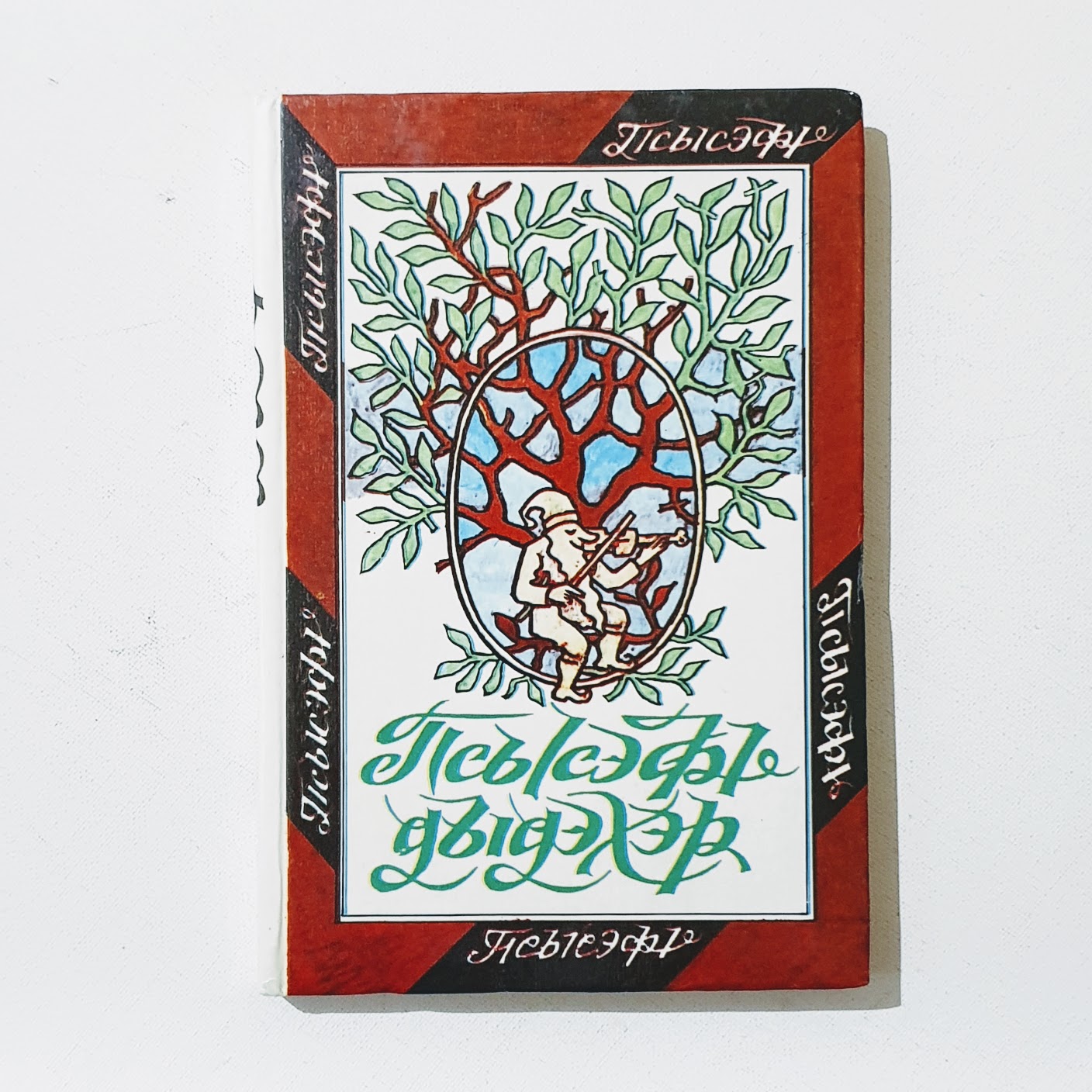

This is one of the stories inside a story collection “Псысэфӏ Дыдэхэр” (Psysef Dydekher) in Kabardian / адыгэбзэ / къэбэрдей адыгэбзэ / къэбэрдейбзэ or East Circassian.

The Kabardian language is a strikingly complex and expressive member of the Northwest Caucasian language family, spoken primarily in the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic of the Russian Federation and by large Circassian diaspora communities. Closely related to Adyghe (West Circassian), Kabardian is renowned for its rich consonantal system—boasting over 50 distinct consonants—and its extreme phonological economy in vowels, typically using just three. Unlike neighbouring languages from the Northeast Caucasian (e.g., Avar, Chechen) or South Caucasian/Kartvelian (e.g., Georgian) families, Kabardian’s grammar is marked by polysynthetic morphology, ergative alignment, and a reliance on prefixes rather than suffixes, reflecting a deep-rooted typological uniqueness in the Caucasus.

Historically, Kabardian evolved in the north-central Caucasus, among the Circassian peoples who, for centuries, maintained a distinct culture of mountain resilience, equestrian skill, clan loyalty, and a fierce warrior code. Their society was intricately hierarchical yet bound by the ancient code of khabze, a customary law dictating honour, hospitality, and conduct. The language flourished in oral poetry, folklore, and ritual speech, embodying collective memory and spiritual wisdom. During the 19th century, as a result of Russian imperial expansion and the brutal Caucasian War, many Kabardians were displaced in what is now termed the Circassian genocide, leading to a vast diaspora and the spread of Kabardian far beyond the Caucasus.

The language’s survival across borders is testimony to the cultural tenacity of its speakers. In modern Kabardino-Balkaria, Kabardian holds official status alongside Russian, and is taught in schools and used in media, though often threatened by Russian linguistic dominance. In diaspora communities, particularly in Turkey, efforts to revive and maintain the language are increasingly seen as central to preserving Circassian identity. For instance, a traditional Kabardian sentence like “Сэ уэрэд сытэр къэкӏуащ” (I saw the man who came) reflects Kabardian’s intricate relative clause structure and verb-driven syntax.

Kabardian shares its deep historical and cultural entanglement with other indigenous Caucasian languages but remains mutually unintelligible with Georgian or Chechen, despite millennia of geographic proximity. While Kartvelian languages like Georgian have elaborate verb systems and literary traditions dating back to antiquity, and Northeast Caucasian tongues like Lezgian or Dargwa boast extensive case systems, Kabardian is set apart by its consonantal richness, prefix-heavy verb morphology, and oral poetic tradition. This unique linguistic fingerprint mirrors the equally distinctive Circassian worldview—one of adaptability, honour, and cultural pride etched into every syllable.