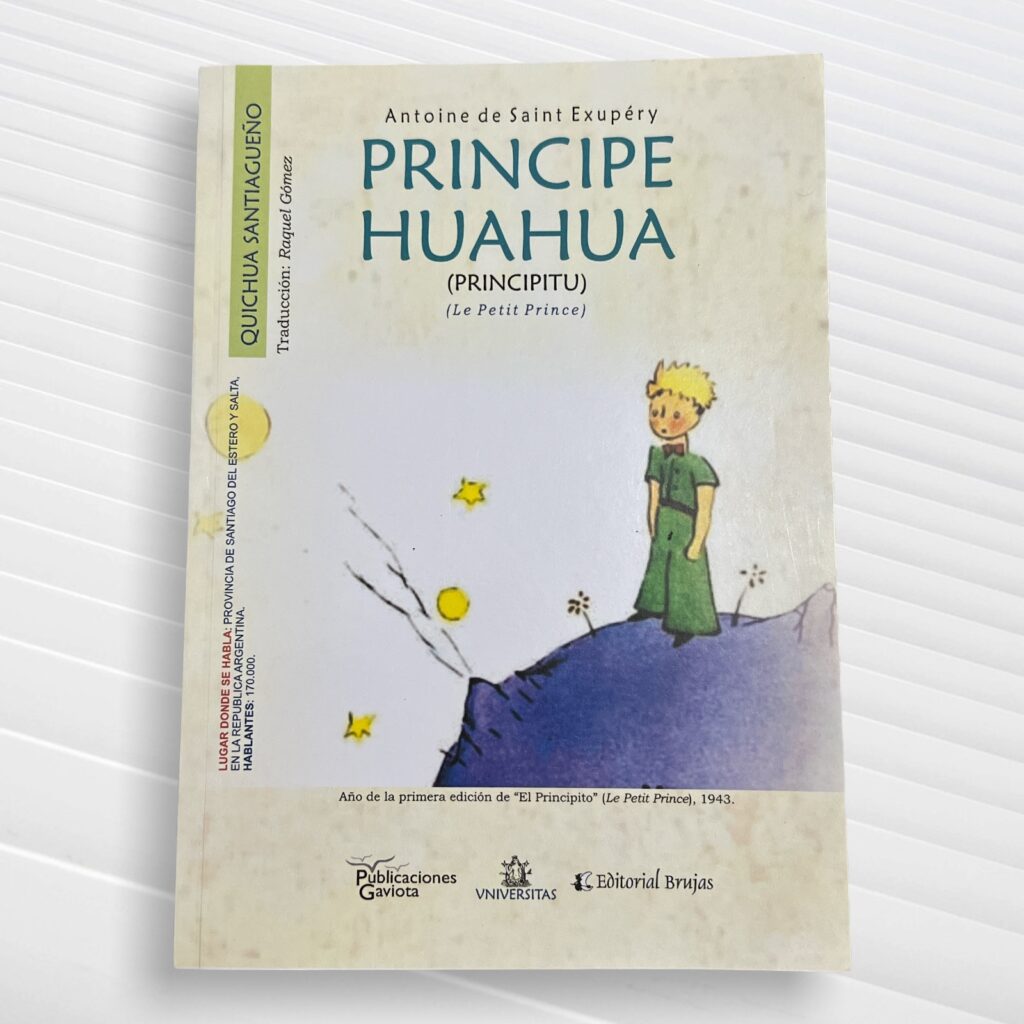

Principe Huahua — in Santiagueño Quechua.

Santiagueño Quechua, also known as Santiago del Estero Quechua, is a uniquely enduring and culturally rich variety of the Quechua language family, spoken in the northern province of Santiago del Estero in Argentina. Remarkably, it represents the southernmost outpost of the Quechua-speaking world, geographically and linguistically far removed from the Andean heartlands of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador. Often considered a member of the Quechua II subgroup, Santiagueño Quechua has diverged significantly due to centuries of isolation, contact with Spanish and local indigenous languages, and the influence of rural Argentine culture. Today, it is a living testament to the deep historical connections between the southern Andes and Argentina’s interior—a linguistic echo of the Inca expansion into the region during the 15th century.

What makes Santiagueño Quechua particularly fascinating is that it has been transmitted for generations without direct ties to a Quechua-speaking homeland, surviving in a non-Andean environment where Spanish has long been dominant. This variety is not mutually intelligible with Central or Northern Quechua dialects, and it has absorbed numerous Spanish loanwords, phonetic adaptations, and local syntactic features. Yet it retains core elements of Quechua structure—such as its agglutinative morphology, evidentiality markers, and vowel harmony—offering linguists a rare example of how indigenous languages evolve in contact with European ones over long periods.

Culturally, Santiagueño Quechua is intimately tied to the mestizo rural communities of northern Argentina, especially in agricultural and pastoral life. It is the language of folk songs, storytelling, and rituals tied to Catholic and pre-Columbian traditions. Although often spoken privately within families or small communities, it carries profound symbolic weight as a marker of heritage, especially in a national context where indigenous languages have historically been marginalised. Local artists and activists have increasingly embraced it as a form of cultural resistance and identity, and it has gained visibility through community radio, education projects, and grassroots poetry.

In relation to other Quechua varieties, Santiagueño stands as a linguistic outlier—distant from its cousins not only geographically but structurally. Yet it remains a part of the broader Quechua identity, a language family that spans six countries and over ten million speakers. Its closest linguistic relatives are found in southern Bolivia, but even these share limited mutual intelligibility. The language’s presence in a Spanish-speaking, non-Andean region highlights the complex and surprising routes by which language and culture can travel and take root.