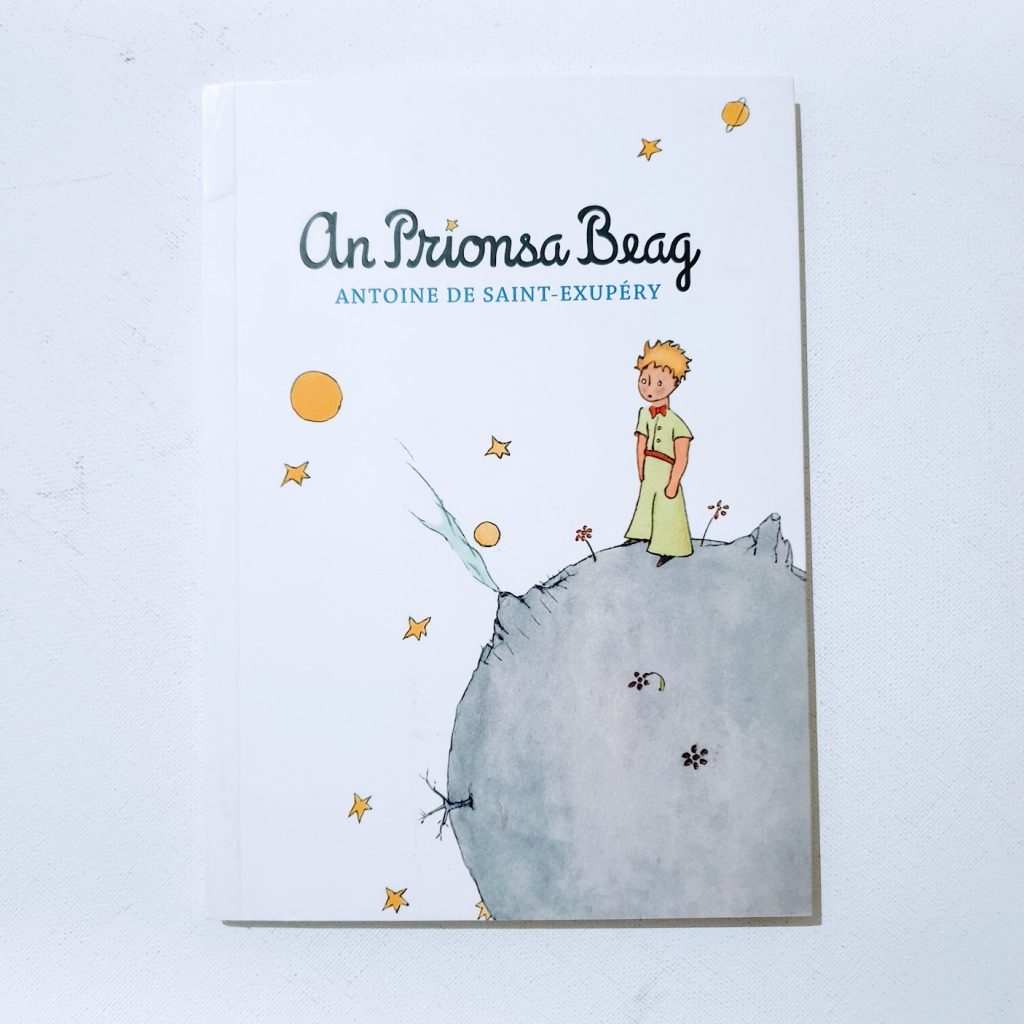

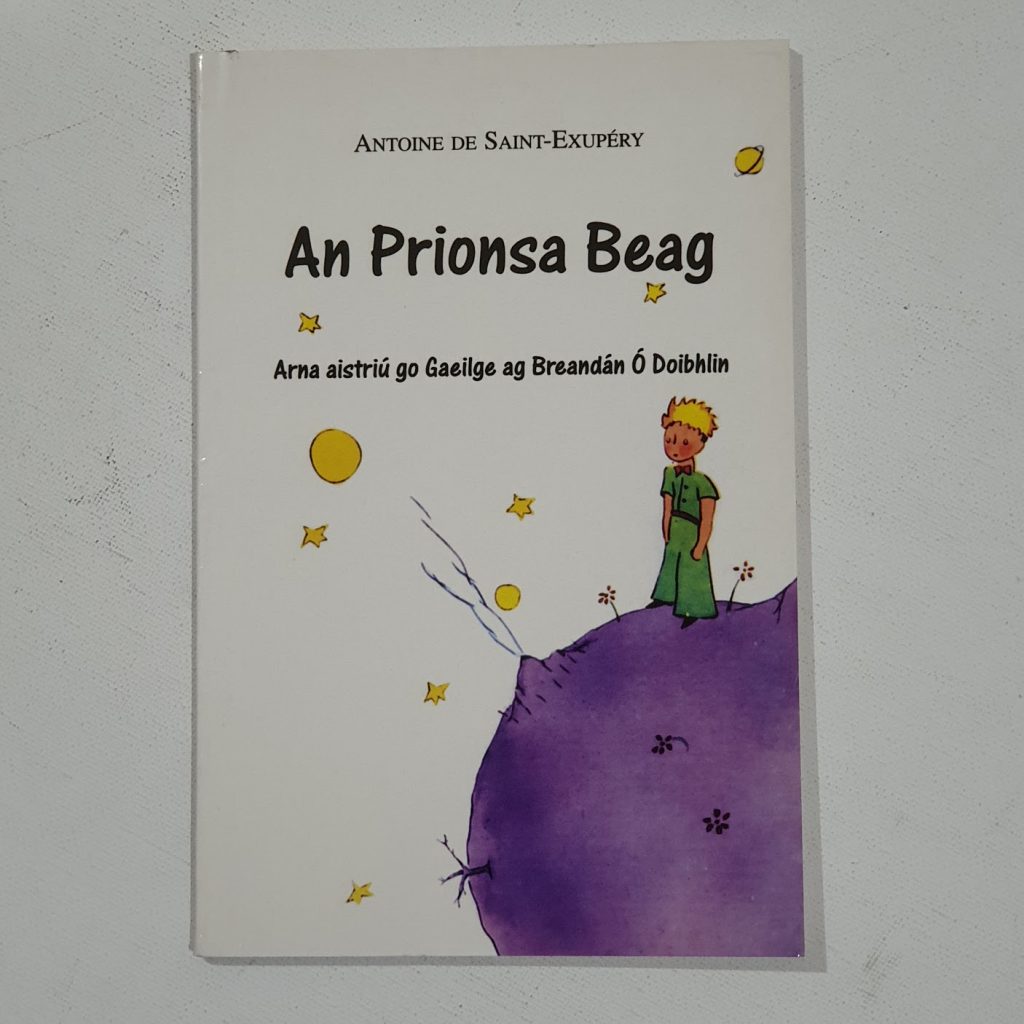

An Prionsa Beag, in an Irish Celtic language used in Ireland.

The Irish language, or Gaeilge, is a poetic and ancient Celtic tongue, native to the island of Ireland and part of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic language family, alongside Scottish Gaelic and Manx. Its origins stretch back over two thousand years, older than English on the island, and its earliest written form—Primitive Irish—can be found inscribed in the mysterious Ogham script on stone pillars dating from the 4th century. Irish flourished during the early medieval period, when Ireland became known as the “Island of Saints and Scholars,” exporting monastic learning and illuminated manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells, across Europe. For centuries, Irish was the dominant language of the people, rich in oral tradition, storytelling, and bardic poetry that wove together myth, history, and satire with stunning linguistic intricacy. However, the language’s fortunes declined under English colonial rule: political suppression, land dispossession, and the trauma of the Great Famine in the 19th century triggered both population loss and a catastrophic shift toward English, especially as economic survival became tied to emigration and anglicisation.

Yet Irish is more than a relic—it is a cultural heartbeat that continues to echo, defiant and lyrical. The language became a central pillar of Ireland’s national identity during the Gaelic Revival of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, closely linked to the struggle for independence and cultural decolonisation. After the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, Irish was declared an official language, and today it remains one of the two national languages of the Republic of Ireland, as well as an official language of the European Union. In education, Irish is compulsory in schools, though fluency levels vary significantly, often depending on exposure outside the classroom. Gaelscoileanna (Irish-medium schools) have grown in popularity, producing a new generation of speakers who connect to Irish not only as a subject but as a living language. In the Gaeltacht regions—sparsely populated Irish-speaking areas along the west coast—the language remains more rooted in daily life, closely tied to rural tradition, music, and a strong sense of community heritage.

Culturally, Irish carries a beauty and complexity that mirrors the emotional depth and rhythm of Irish identity itself. The language is famed for its indirectness, metaphor, and sensitivity to mood and tone—qualities that lend themselves to storytelling, sean-nós singing, and the distinctive lilt of Irish poetry and prose. It retains a close kinship with Scottish Gaelic, with which it shares much vocabulary and grammar, and a distant but spiritual connection to Welsh, Cornish, and Breton, its Brythonic Celtic cousins. Politically, the language still sparks debate—between those who see it as a vital expression of post-colonial dignity and cultural resilience, and those who question its practicality in an English-dominated global context. Nevertheless, its recent revival in music, literature, film, and online culture reveals a deepening appreciation, especially among younger generations, for Irish as not merely a language but a repository of worldview, humour, and memory. To speak Irish today is to participate in a cultural continuum—at once endangered and enduring, mournful and musical—woven into the very fabric of Ireland’s land, past, and evolving soul.