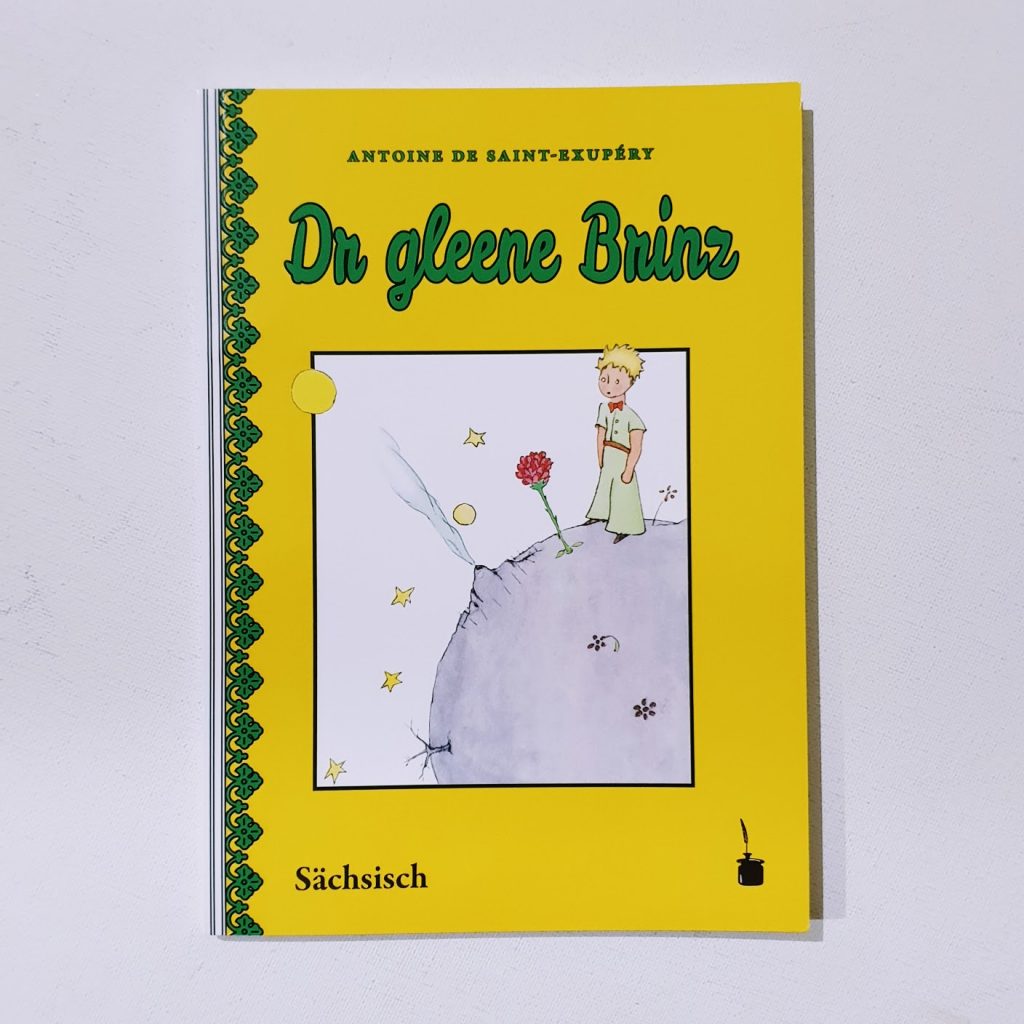

Dr Gleene Brins — in Saxon or Upper Saxon (Obersächsisch).

Upper Saxon German, or Obersächsisch, is a regional variety of High German spoken predominantly in the Free State of Saxony, especially around cities like Dresden, Leipzig, and Chemnitz. Often mischaracterised as merely a “thick accent,” Upper Saxon is in fact a distinct dialect with deep historical roots and rich cultural resonance. It developed in the early Middle Ages from the linguistic melting pot of Slavic and Frankish-Germanic interactions in what was then the eastern frontier of the Holy Roman Empire. As part of the East Central German dialect continuum, Upper Saxon shares features with Thuringian and Silesian, but also bears unique phonetic characteristics—such as a sing-song intonation and vowel shifts—that have long made it stand out among German dialects, often to the comic or critical delight of speakers from other regions.

Culturally, the Upper Saxon dialect is inseparable from the legacy of Saxony itself, once a flourishing centre of art, science, and music in the German-speaking world. During the Baroque period, Dresden—then called the “Florence on the Elbe”—became a cultural beacon, and the dialect that developed around it carried both the refinement of courtly speech and the earthy humour of its working-class neighbourhoods. Though often satirised in national media for its perceived quaintness, Upper Saxon is cherished locally for its expressiveness and emotional nuance. It features prominently in regional theatre, folk songs, and cabaret, where it lends a flavour of local pride and intimacy. Relations to other Germanic languages are also intriguing: while clearly part of the High German group, Upper Saxon retains some older forms lost in Standard German and shares historical affinities with Yiddish and Middle High German through shared phonological developments.

In modern times, the dialect has faced pressure from Standard German and the socio-economic shifts following reunification, yet it survives in family homes, village pubs, and a growing body of dialect literature and media. Speaking Upper Saxon today is both a cultural marker and a subtle act of resistance—an assertion of identity rooted in a region known for both its intellectual ferment and its salt-of-the-earth sensibility. It is the language of both Bach and the backstreets, carrying within it centuries of adaptation, resilience, and the quietly defiant charm of Saxony’s people.