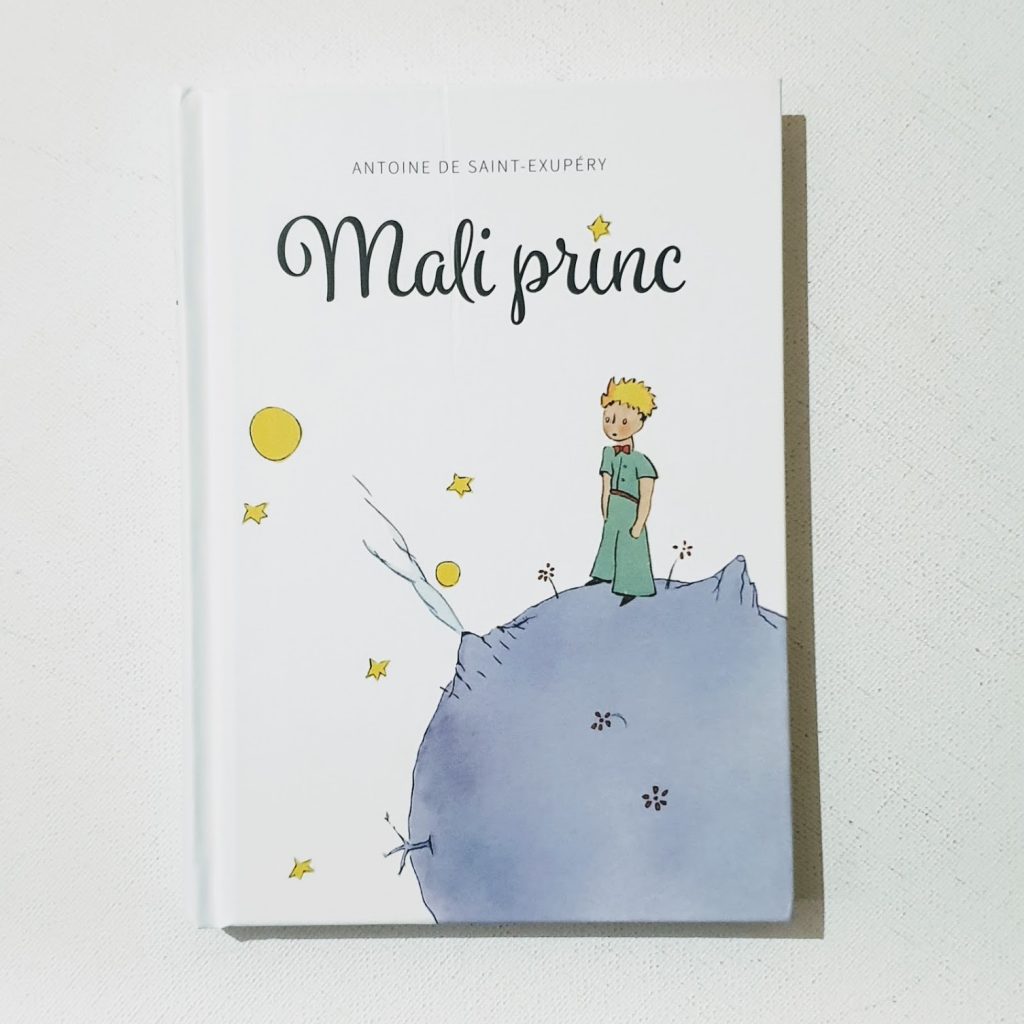

Mali Princ — in Slovenian language.

The Slovene language, or slovenščina, is a South Slavic tongue with a soul as rich and complex as the alpine landscapes and river valleys where it is spoken. As the official language of Slovenia and one of the few surviving Slavic languages to retain a full dual grammatical number (used not just for singular and plural, but also for two people or things), Slovene offers a glimpse into the archaic elegance of the Proto-Slavic past. It has evolved through a millennia-long journey shaped by Roman Catholic liturgy, Habsburg imperial rule, and Yugoslav socialist modernity, yet it remains unmistakably Slovenian—intimate, poetic, and community-rooted. Its first known written words appeared in the Freising Manuscripts around the 10th century, making Slovene one of the earliest documented Slavic languages, and later saw a blossoming of religious and literary expression in the 16th century, when Protestant reformer Primož Trubar printed the first Slovene books to assert cultural and linguistic identity through the written word.

What makes Slovene society particularly interesting is its fierce pride in local dialects—dozens of them flourish across the country, from the Karst to the Drava plain—so much so that Slovenians often identify as much by their dialect as by their nationality. This linguistic mosaic mirrors a culture that values both individuality and harmony, evident in the careful balance Slovenians maintain between tradition and innovation. Their customs, such as kurentovanje (a pagan-rooted spring festival where sheepskin-clad figures drive out winter), showcase a deep connection to nature and folklore. Music, too, plays a key role, from alpine harmonies and polkas to the refined cadences of Slovene poetry, which holds a special place in national identity—so much so that a poet, France Prešeren, is the author of the national anthem. Slovene is not just a means of communication but a vessel of poetic resilience, a guardian of memory, and a cultural compass for a nation that has always stood at the crossroads of Germanic, Romance, and Slavic worlds—yet has never lost its distinct voice.