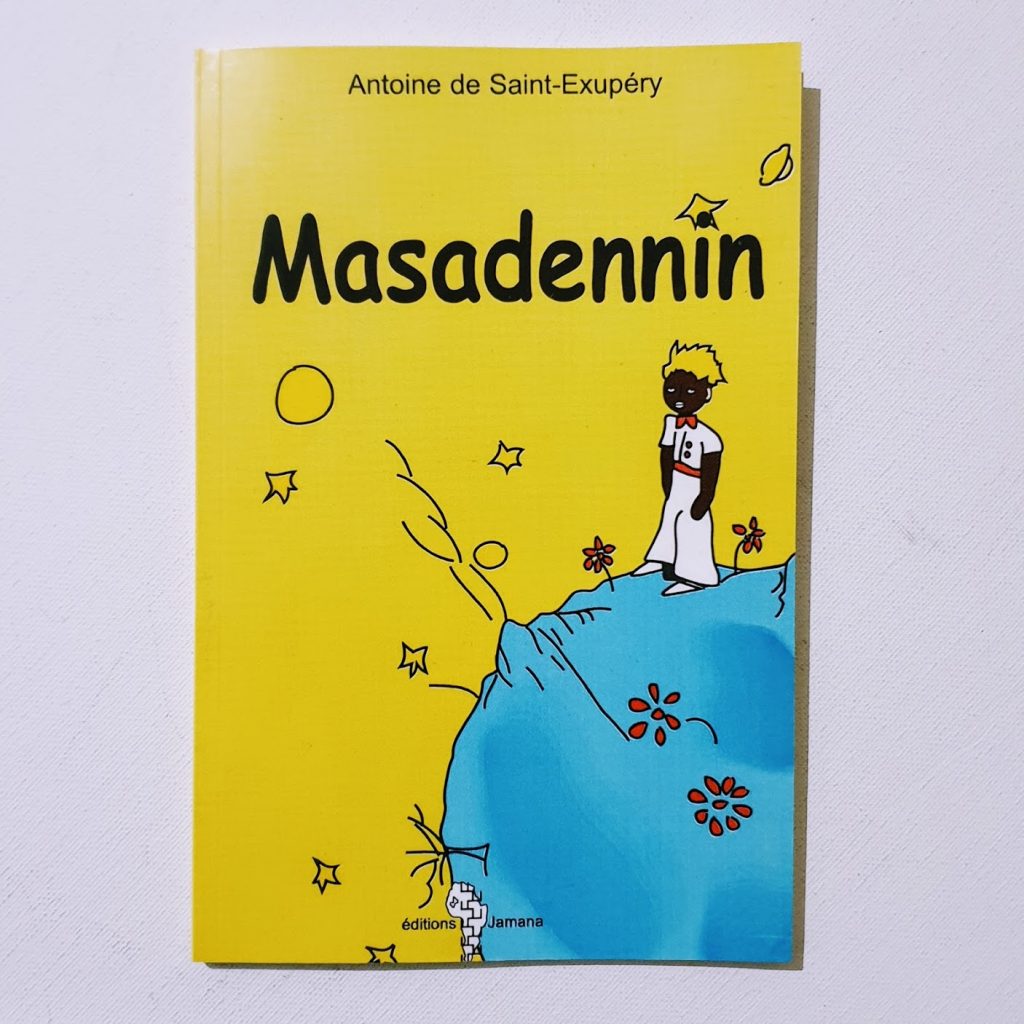

Masadennin — in the Bambara language.

Bambara, or Bamanankan, is the most widely spoken language in Mali and a vital cultural artery of West Africa, serving both as a native tongue of the Bambara people and as a lingua franca across much of the country. A member of the Mande branch of the Niger-Congo language family, Bambara is closely related to languages such as Dioula, Malinké, and Mandinka, with mutual intelligibility that allows communication across ethnic and national boundaries from Senegal to Burkina Faso. With its agglutinative structure, subject-object-verb word order, and tonal distinctions, Bambara is linguistically rich and rhythmically expressive, lending itself naturally to oral storytelling, praise poetry, and music. Historically, it traces its roots to the once-mighty Mali Empire (13th–16th centuries), where Mande languages formed the administrative and cultural backbone of one of Africa’s most sophisticated pre-colonial civilisations, centred on cities like Timbuktu and Djenné—hubs of Islamic scholarship, commerce, and trans-Saharan exchange.

Bambara-speaking societies are grounded in a deeply oral tradition, where the jeliw (griots) have long served as custodians of history, genealogy, ethics, and social cohesion. These hereditary bards wield language with reverence and artistry, passing on epic tales of Sundiata Keita and the heroic age of empire. Even today, Bambara lives vibrantly through proverbs, ceremonial speech, and popular music, especially in Afro-Manding genres, which blend traditional instrumentation like the ngoni and balafon with modern expression. The language also encodes a complex worldview shaped by nyama (spiritual force), communal ethics, and agricultural rhythms, with rich vocabulary for cultivation, seasonal changes, and social roles. This cosmology continues to inform daily life in both rural and urban settings, where social structures are interwoven with traditional values, Islamic faith, and a growing modern consciousness.

Bambara’s status has been both empowering and paradoxical. Though not officially designated as Mali’s national language—that role is reserved for French—it functions in practice as the country’s unifying linguistic thread. It is used in radio broadcasts, informal education, religious discourse, and increasingly in literature and film. Yet, like many African languages, it faces institutional marginalisation, especially in formal education and governance, where French still dominates. Post-independence language policies have made attempts to integrate Bambara into literacy campaigns and primary education, with the development of a Latin-based orthography, but political instability and underfunding have hindered these efforts. Nevertheless, Bambara remains a linguistic heartbeat of national identity, resisting the legacy of colonial language hierarchies and carrying forward the living spirit of Mande civilisation.

In relation to its linguistic cousins, Bambara is not simply a dialect within a family but a central node in a pan-West African linguistic network. Its mutual intelligibility with Dioula (spoken in Côte d’Ivoire and Burkina Faso) and Mandinka (widespread in The Gambia and Guinea) makes it a powerful medium of transnational cultural continuity.