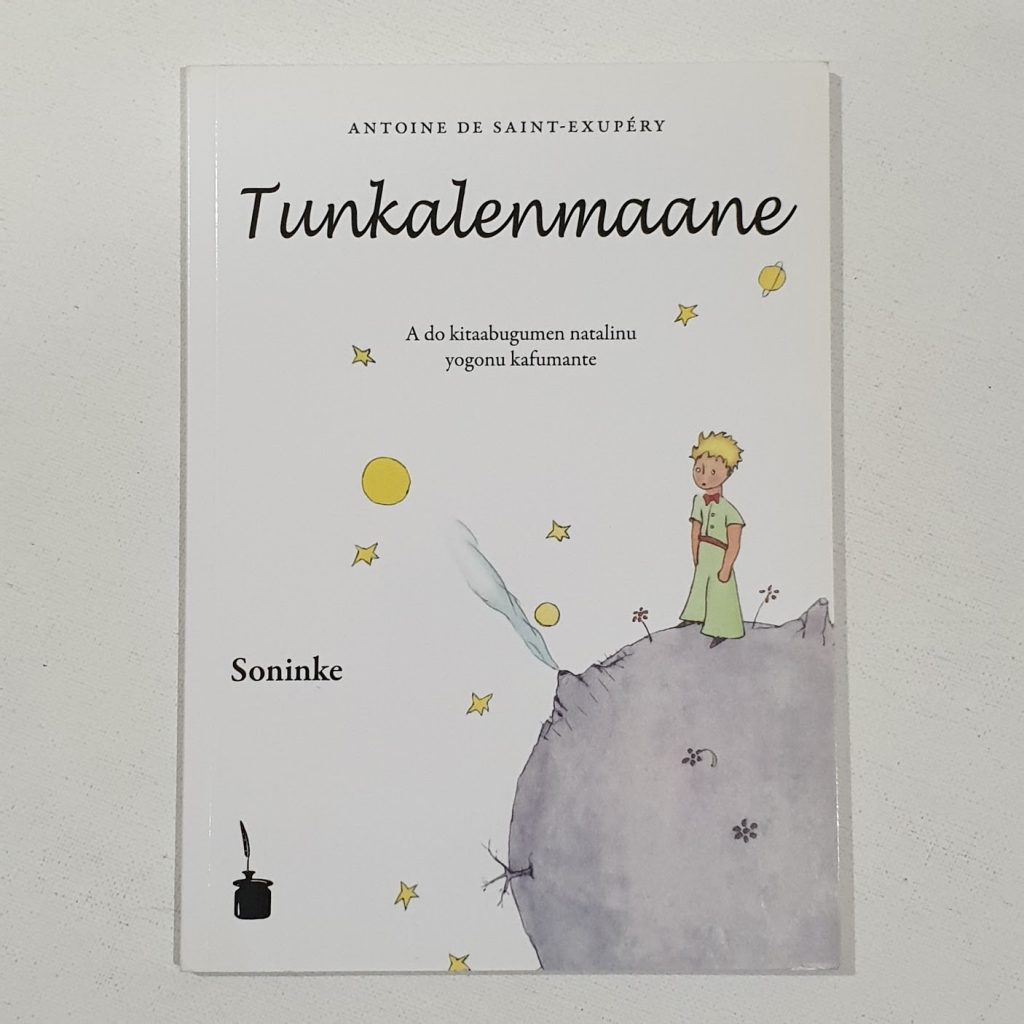

Tunkalenmaane — in Soninke, a Mande language spoken by the Soninke people of Africa. The language has an estimated 1 million speakers, primarily located in Mali, and also (in order of numerical importance of the communities) in Senegal, Ivory Coast, The Gambia, Mauritania, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and Ghana. It enjoys the status of a national language in Mali, Senegal, The Gambia and Mauritania.

The language is relatively homogeneous, with only slight phonological, lexical, and grammatical variations.