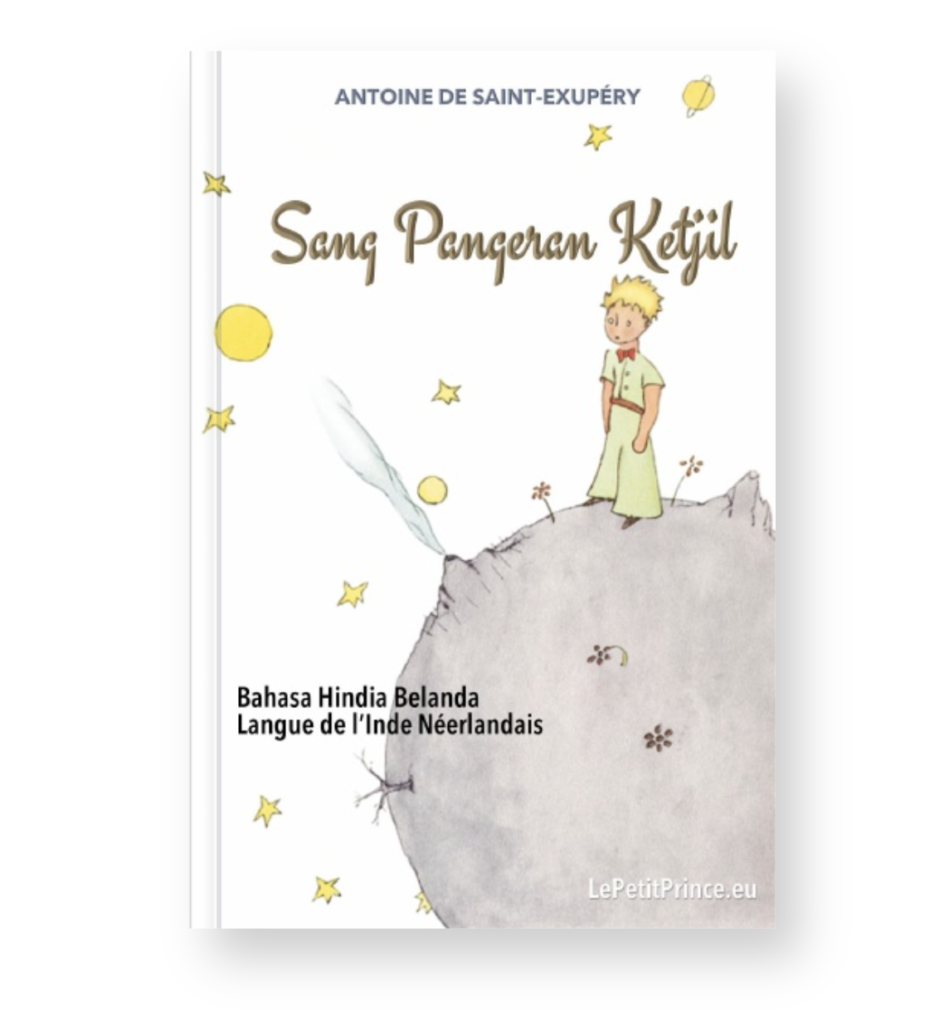

Sang Pangeran Ketjil — in old Indonesian language style, written in old Van Ophuijsen orthography used in Indonesia before the independence.

The Van Ophuijsen orthography, named after Charles Adriaan van Ophuijsen, a Dutch linguist and colonial civil servant, represents the first formal attempt to standardise the writing system of the Malay language in the Latin script during the Dutch East Indies era. Introduced in 1901 through his Kitab Logat Melajoe, this orthographic system laid the foundation for what would eventually evolve into modern Indonesian. Prior to this, Malay—already functioning as a regional lingua franca—had been written in Jawi (an adapted Arabic script) or various inconsistent Latin-based spellings. Van Ophuijsen’s system, developed with the help of native scholars such as Raja Ali Haji and Engku Nawawi, marked a pivotal moment in colonial linguistic policy: a fusion of Western philological rigidity with indigenous phonology. It was a colonial tool for control and instruction, but it also served as a gateway to literacy for the native elite and a seed for later nationalist consciousness.

The orthography itself was characterised by a hybrid Dutch-Malay phonetic logic. For example, it used “oe” for the /u/ sound (as in goeroe for guru), “tj” for /c/ (as in ketjil for kecil), and “dj” for /j/ (as in djalan for jalan). This reflected Dutch linguistic conventions but often confused or alienated native learners due to its foreign orthographic flavour. Nevertheless, it became the standard for schools, legal documents, and publications across the archipelago, shaping the way Malay—and later Indonesian—was taught and internalised. Importantly, this orthography helped establish a bridge between spoken and written forms of Malay, elevating it from a marketplace tongue to a language of administration and eventually, intellectual discourse.

The Van Ophuijsen system mirrored the power dynamics of the time: it was a colonial imposition but one that paradoxically enabled local elites to master the tools of modernity. Through schools, missionary education, and nationalist presses, this script seeded a literate, Malay-speaking class who would go on to articulate visions of independence and unity. In cultural terms, it helped standardise spelling in printed literature, enabling the emergence of modern Indonesian prose and poetry. Writers such as Merari Siregar and Abdul Muis published their early works using this orthography, marking the birth of Indonesian literary modernism under a colonial spell.

The Van Ophuijsen orthography was eventually replaced in the 1947 Republican Spelling System and later refined in the Ejaan Yang Disempurnakan (EYD) of 1972. These changes removed Dutch orthographic remnants in favour of more phonetic and accessible forms—for instance, “oe” became “u”, “tj” became “c”, and “dj” became “j”. This linguistic transition was not merely technical—it was a decolonial and nationalistic act, as the Republic sought to craft a modern identity distinct from colonial legacies. Still, the legacy of Van Ophuijsen endures in archival materials, older literature, and the collective memory of Indonesia’s linguistic journey.

In relation to modern Indonesian, Van Ophuijsen’s orthography may seem quaint, even cumbersome, but it was a vital scaffolding in the construction of Bahasa Indonesia as a national language. It represents a moment when colonial intent and native aspiration met in the domain of language—a site of control, resistance, and eventual transformation. For many Indonesians, especially those engaged in literary, linguistic, or historical study, Van Ophuijsen’s orthography is a reminder of how language evolves not just through logic and sound, but through power, politics, and the unyielding desire to express one’s identity in a changing world.