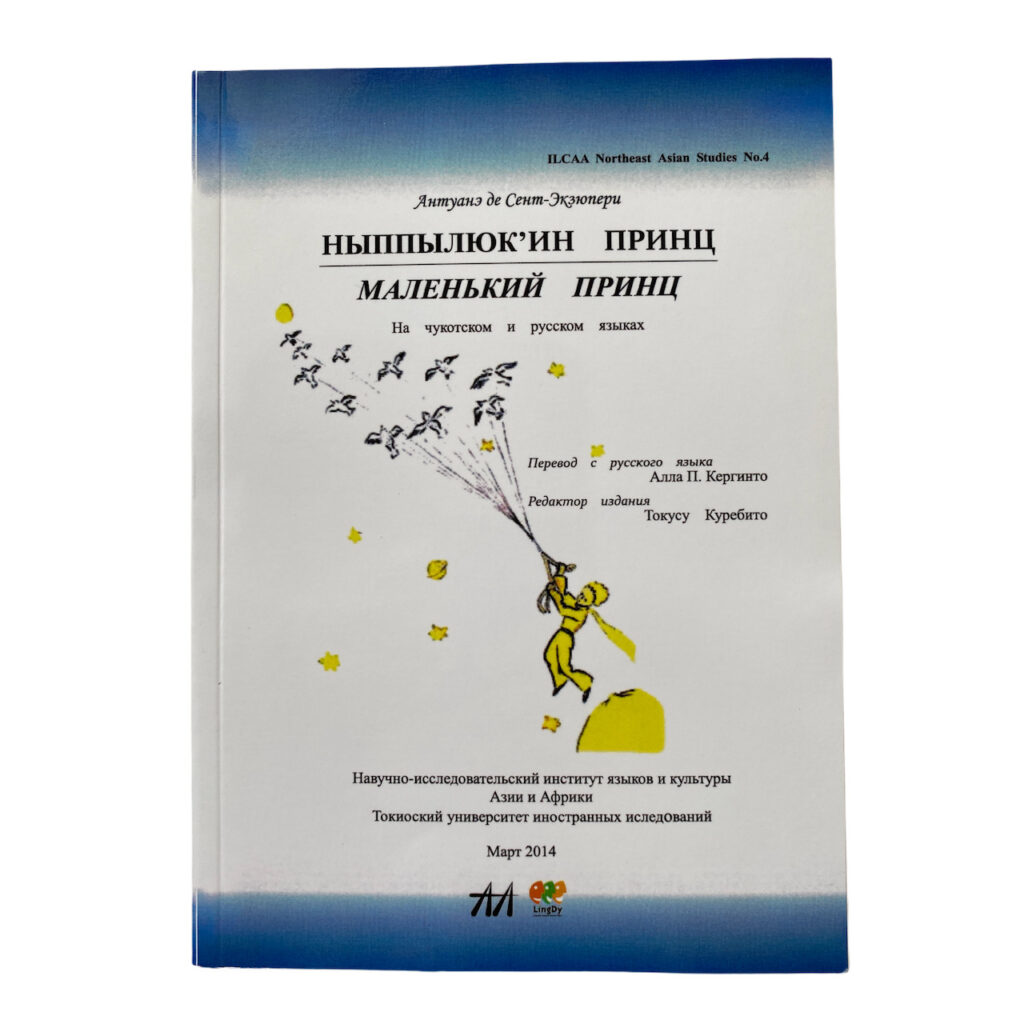

Ныппылюк’ин Принц / Nyppylyuk’in Prints — in Chukchi languange.

The Chukchi language, known natively as Luoravetlan (ԓыгъоравэтԓьан), is a striking and ancient tongue spoken by the Chukchi people of Chukotka, the windswept northeastern tip of Siberia that faces Alaska across the Bering Strait. It belongs to the small and isolated Chukotko-Kamchatkan language family, which includes Koryak, Alutor, and the now critically endangered or extinct Itelmen, all spoken (or formerly spoken) in eastern Siberia. These languages, though distinct, share a deep grammatical structure and likely evolved from a common ancestor, reflecting ancient population movements across the Kamchatka Peninsula and surrounding regions. While Chukchi and Koryak are mutually unintelligible, they exhibit similarities in ergative alignment, vowel harmony, and polysynthetic morphology, indicating a shared linguistic lineage.

Chukchi itself has long stood in contact with neighbouring Eskimo-Aleut, Yukaghir, and Even (Tungusic) languages, with which it shares some typological features due to centuries of Arctic interaction—particularly through trade, migration, and cultural exchange across tundra, taiga, and ice-covered coasts. Typologically, Chukchi is remarkable: it is ergative, highly inflected, and noted for consonant alternation, complex verb structures, and a vocabulary deeply rooted in environmental observation and spiritual cosmology.

Historically, the Chukchi were semi-nomadic reindeer herders and coastal hunters, whose lives followed the harsh but rhythmic cycles of the Arctic year. Their language, entirely oral until the 20th century, reflects this world intimately—expressing nuanced distinctions in ice, wind, animal behaviour, and natural phenomena. Chukchi oral tradition, passed down by storytellers and elders, contains myths, humour, genealogies, and teachings bound to both survival and identity. Animism and the belief in animal-persons and spirit worlds shape the mythopoetic use of language, especially in ritual storytelling and chants.

A Cyrillic-based writing system was introduced during the Soviet period, and Chukchi enjoyed a brief cultural renaissance with newspapers, radio programmes, and educational material published in the language. However, decades of Russification, along with migration to urban centres and the dominance of Russian in schools, have led to sharp declines in daily use. Most fluent speakers today are elderly, though revitalisation efforts—including Chukchi-language schools, dictionaries, and oral history recordings—are gaining momentum, driven by community pride and cultural resilience.

Though the Chukotko-Kamchatkan family as a whole is endangered, Chukchi remains the most widely spoken of its group, maintaining cultural salience in reindeer-herding communities and coastal settlements. It stands apart linguistically from more well-known Siberian languages, such as Even or Nenets, and it is unrelated to Uralic languages, despite their geographic proximity. To hear or learn Chukchi is to engage with one of the most unique linguistic legacies of the Arctic—a voice shaped by millennia of adaptation, storytelling, and reverence for a land where nature and language have always been in deep conversation.