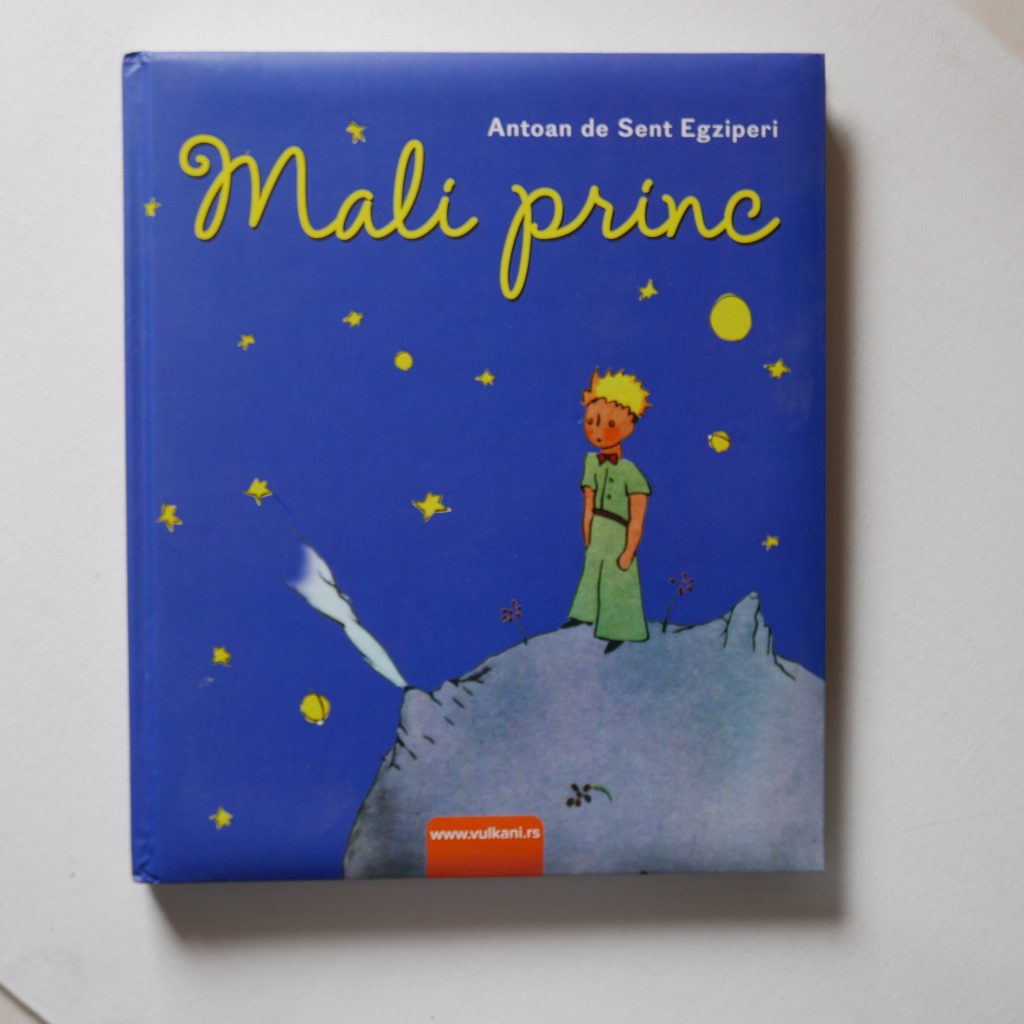

Mali Princ — in Serbian.

The Serbian language occupies a distinctive place within the Slavic linguistic landscape through its sustained and fully functional use of two scripts: Cyrillic and Latin. This dual-script system is neither transitional nor symbolic; it is an integral feature of modern Serbian literacy. Cyrillic, constitutionally recognised and historically rooted in Orthodox Christian tradition, coexists seamlessly with the Latin script, which reflects centuries of cultural and political interaction with Central and Western Europe. The result is a language community uniquely comfortable moving between scripts without perceiving the shift as a change in identity or meaning.

Historically, Serbian developed at a cultural crossroads shaped by Byzantium, the medieval Slavic world, and later the Ottoman and Habsburg empires. Early Serbian literacy grew from Church Slavonic and the Cyrillic manuscript tradition, placing it firmly within the Eastern Orthodox cultural sphere alongside Bulgarian and Russian. From the eighteenth century onwards, increasing exposure to Latin-script environments influenced administration, education, and publishing. The nineteenth-century reforms led by Vuk Karadžić were decisive: by establishing a strictly phonemic orthography, i.e. write as you speak, he laid the foundation for a modern standard that could be expressed with equal clarity in both scripts.

Serbia’s historical and cultural uniqueness lies in its ability to absorb divergent influences without linguistic rupture. Geographically and culturally positioned between Orthodox, Catholic, and Islamic civilisations, Serbian developed in close contact with neighbouring languages such as Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin, Slovenian, Bulgarian, and Macedonian. While these languages share significant structural similarities, Serbian stands apart in its balanced scriptal duality and its uninterrupted continuity of Cyrillic usage in everyday life. This dual inheritance has fostered a linguistic culture marked by flexibility, layered identity, and a strong sense of historical memory.

In terms of broader influence, Serbian has played an important role within the South Slavic linguistic continuum and beyond. Its nineteenth-century standardisation informed parallel developments in related languages, particularly within the shared Serbo-Croatian linguistic space. Serbian folk poetry and epic traditions, meticulously collected and published, shaped European Slavic studies and influenced comparative linguistics across the continent. Moreover, Serbia’s ongoing commitment to Cyrillic as a modern, functional script has contributed to the resilience and prestige of Cyrillic across the Slavic world. In an era inclined towards uniformity, the Serbian language demonstrates that linguistic plurality, when historically grounded and intellectually disciplined, can be a source of enduring strength rather than division.