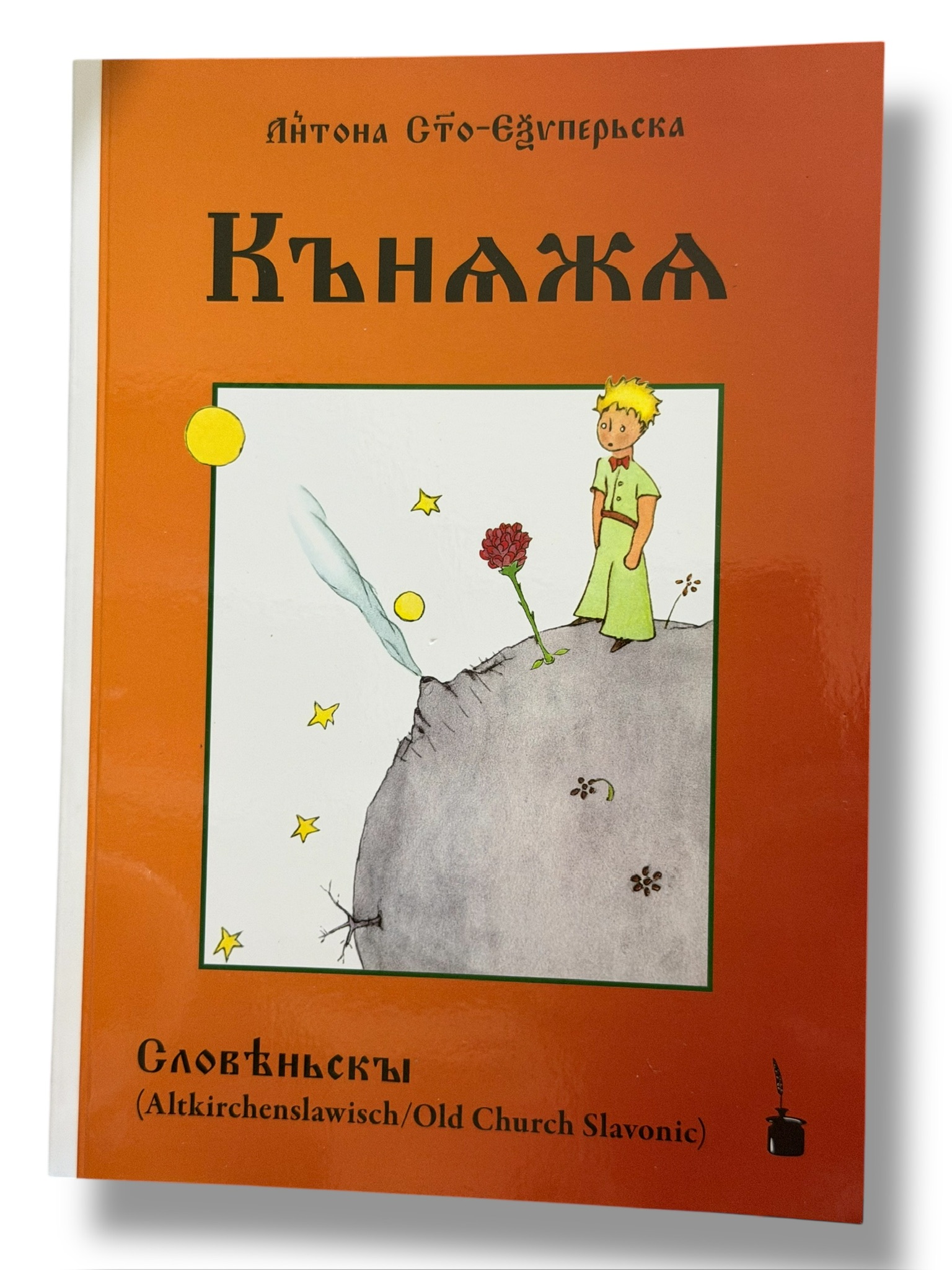

Кънажа — in Old Church Slavonic.

Словѣньскы (Slovensky) or Old Church Slavonic is the earliest attested Slavic literary language, deliberately crafted in the ninth century as a vehicle for Christian theology, administration, and education. It was codified by the Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius, whose objective was both practical and revolutionary: to render sacred texts intelligible to Slavic peoples in their own tongue. Drawing primarily on South Slavic dialects spoken around Thessaloniki, Old Church Slavonic achieved something rare in medieval Europe, i.e. a learned language born not from imperial Latinisation, but from linguistic accommodation. In doing so, it established a cultural precedent that language could be a conduit of dignity rather than domination.

The scriptural history of Old Church Slavonic is inseparable from the evolution of the Cyrillic script. While the earliest translations were likely written in the Glagolitic script, the emergence of Cyrillic soon followed, synthesising Greek uncial forms with additional letters to represent Slavic phonology. Old Church Slavonic functioned as the testing ground in which Cyrillic matured: orthographic conventions, diacritics, and specialised letters such as ѣ (yat), ъ, and ь were refined through sustained liturgical and scholarly use. Without this disciplined linguistic laboratory, Cyrillic would have lacked the structural coherence that enabled its later expansion across Eastern Europe and Eurasia.

The influence of Old Church Slavonic on the Slavic languages is profound and enduring. It supplied not only a vast theological and philosophical vocabulary, but also syntactic and stylistic models that shaped written expression in Bulgarian, Serbian, Russian, Ukrainian, and beyond. Even where vernaculars diverged sharply in phonology and grammar, Church Slavonic layers persisted as markers of register, solemnity, and intellectual authority. Moreover, its impact extended indirectly to neighbouring non-Slavic traditions, most notably Romanian, through ecclesiastical administration and manuscript culture, demonstrating that its reach was cultural rather than merely linguistic.

In the modern world, Old Church Slavonic no longer functions as a spoken language, yet it remains very much alive. It continues to serve as the liturgical language of several Eastern Orthodox Churches, anchoring contemporary worship in a millennium of textual continuity. Beyond religion, it occupies a central place in historical linguistics, palaeography, and comparative philology, offering scholars an indispensable window into the early Slavic mind.