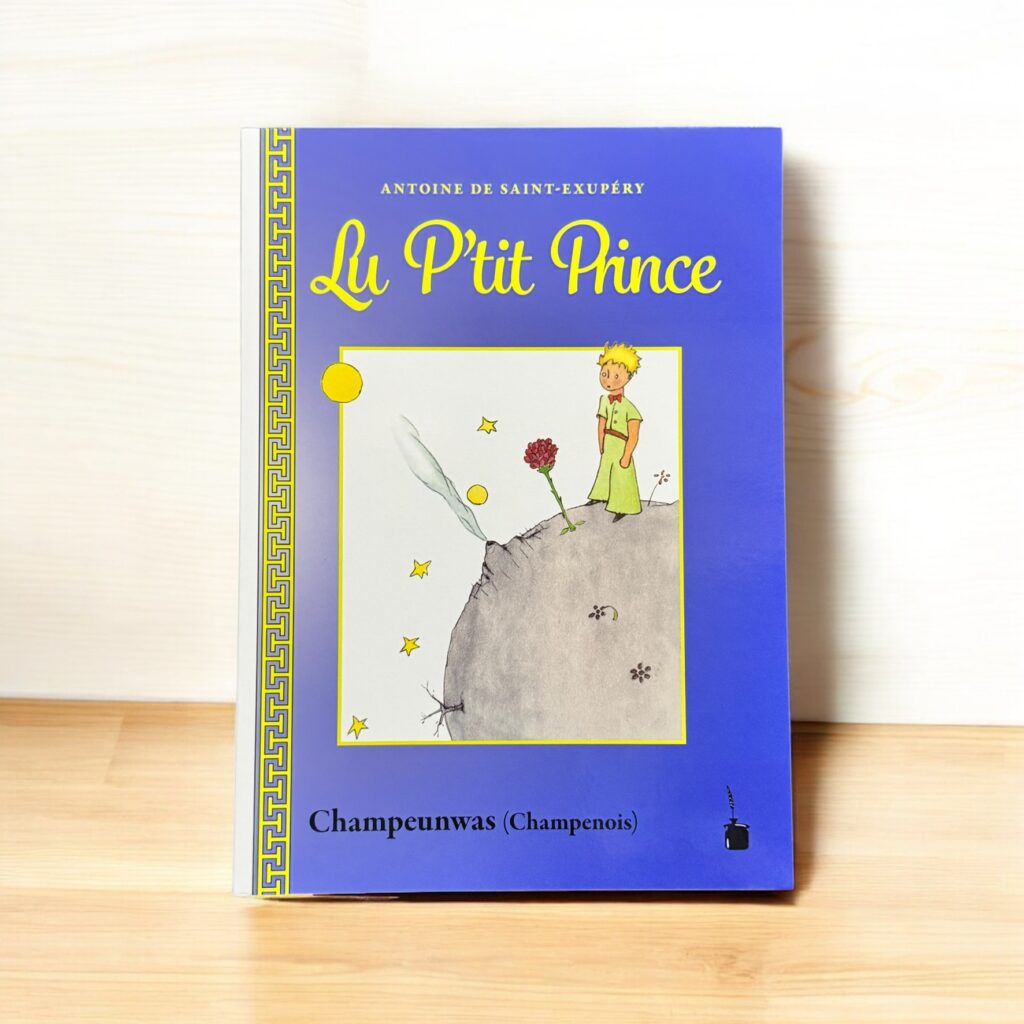

Lu P’tit Prince — in Champenois.

Champenois is a Romance language, or more precisely, a langue d’oïl variety, traditionally spoken in the Champagne region of northeastern France—a land renowned worldwide for its sparkling wine, but also quietly rich in linguistic and cultural heritage. Champenois emerged in the medieval period as one of several regional tongues descended from Vulgar Latin, shaped by the early Frankish presence and the evolving Romance substrate that also gave rise to neighbouring dialects like Picard, Walloon, and Lorrain. It is closely related to Francien, the dialect spoken around Paris that would eventually form the backbone of modern Standard French, but retains distinct phonological, lexical, and grammatical features, many of which harken back to the local history of Champagne’s towns, abbeys, and rural villages.

Historically, Champenois flourished during the High Middle Ages when Champagne was a cultural and commercial crossroads, famous for its fairs that attracted merchants and artisans from across Europe. Medieval poets and clerics, such as Chrétien de Troyes, are sometimes associated with the region, and it is likely that local forms of speech infused the literary culture of the time. While Standard French gradually expanded its reach through royal centralisation, legal codification, and later the educational policies of the French Republic, Champenois survived in the countryside, embedded in oral traditions, folktales, songs, and local theatrical forms. It carries the earthy humour, sharp wit, and pragmatic worldview of the rural Champenois people, expressed through distinctive idioms and colourful expressions that differ markedly from the polished language of Paris.

Culturally, Champenois-speaking communities have long preserved a vibrant sense of local identity, celebrated through festivals, communal rituals, and culinary traditions deeply tied to the land—not least the famed Champagne vineyards, but also local cheeses, hams, and hearty stews. In the past, these communities maintained close ties with speakers of neighbouring langues d’oïl, sharing linguistic features and cross-border affinities with dialects in Belgium and Luxembourg, shaped by centuries of Frankish, Burgundian, and Carolingian influence. Yet, like many regional languages in France, Champenois has faced significant decline over the past two centuries, increasingly displaced by Standard French, especially after the centralised language policies of the Third Republic and the homogenising forces of mass media.

Within the broader context of the Romance language family, Champenois stands as a linguistic bridge—bearing the imprint of both Latin roots and Germanic overlays from the early medieval Frankish settlements. It offers a glimpse into a pre-modern France that was far more linguistically diverse than the standardised republic we know today, and to speak or hear Champenois now is to connect with a world of vineyards, stone villages, and oral memory, where language was a living reflection of local landscape, history, and communal life.